Both the Quran and hadith make reference to witchcraft and the evil eye as well as to supernatural beings known in Arabic as jinn (the origin of the English word genie).22

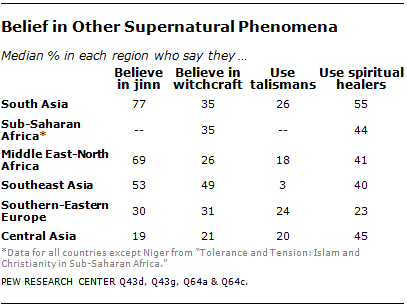

To gauge how widespread belief in these supernatural forces is today, the survey asked Muslims separate questions about witchcraft, jinn and the evil eye (defined in the survey as the belief that certain people can cast curses or spells that cause bad things to happen). In most of the countries surveyed, roughly half or more Muslims affirm that jinn exist and that the evil eye is real. Belief in sorcery is somewhat less common: half or more Muslims in nine of the countries included in the study say they believe in witchcraft. At the same time, however, most Muslims agree that Islam forbids appealing to jinn or using sorcery. As will be discussed in Chapter 6, in all but one country surveyed, no more than one-in-five say that Islam condones people appealing to jinn. Similarly low percentages say the same about the use of sorcery (see Appeals to Jinn in Chapter 6).

Islamic tradition also holds that Muslims should rely on God alone to keep them safe from sorcery and malicious spirits rather than resorting to talismans, which are charms or amulets bearing symbols or precious stones believed to have magical powers, or other means of protection. Perhaps reflecting the influence of this Islamic teaching, a large majority of Muslims in most countries say they do not possess talismans or other protective objects. The use of talismans is most widespread in Pakistan (41%) and Albania (39%), while in other countries fewer than three-in-ten Muslims say they wear talismans or precious stones for protection. Although using objects specifically to ward off the evil eye is somewhat more common, only in Azerbaijan (74%) and Kazakhstan (54%) do more than half the Muslims surveyed say they rely on objects for this purpose.

Reliance on traditional religious healers is most prevalent among Muslims in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, with roughly two-thirds or more in Senegal (73%), Chad (68%) and Afghanistan (66%) saying they have turned to traditional healers to help cure someone who is ill.

Jinn

According to the Quran, God created jinn as well as angels and humans. Belief in jinn is relatively widespread – in 13 of 23 countries where the question was asked, more than half of Muslims believe in these supernatural beings.

In the South Asian countries surveyed, at least seven-in-ten Muslims affirm that jinn exist, including 84% in Bangladesh. In Southeast Asia, a similar proportion of Malaysian Muslims (77%) believe in jinn, while fewer in Indonesia (53%) and Thailand (47%) share this belief.

Across the Middle Eastern and North African nations surveyed, belief in jinn ranges from 86% in Morocco to 55% in Iraq.

Overall, Muslims in Central Asia and across Southern and Eastern Europe (Russia and the Balkans) are least likely to say that jinn are real. In Central Asia, Turkey is the only country where a majority (63%) of Muslims believe in jinn. Elsewhere in Central Asia, about a fifth or fewer Muslims accept the existence of jinn. In Southern and Eastern Europe, fewer than four-in-ten in any country surveyed believe in these supernatural beings.

In general, Muslims who pray several times a day are more likely to believe in jinn. For example, in Russia, 62% of those who pray more than once a day say that jinn exist, compared with 24% of those who pray less often. A similar gap also appears in Lebanon (+25 percentage points), Malaysia (+24) and Afghanistan (+21).

The survey also asked if respondents had ever seen jinn. In 21 of the 23 countries where the question was asked, fewer than one-in-ten report having seen jinn, while the proportion is 12% in Bangladesh and 10% in Lebanon.

It is important to note that while belief in jinn is widespread, relatively few Muslims in the countries surveyed believe it is an acceptable part of Islamic tradition to make offerings to jinn. As discussed in Chapter 6, Bangladesh is the only country surveyed in which more than a fifth of Muslims (28%) say appeals to jinn are acceptable. In 18 of the countries, no more than one-in-ten say this is an acceptable practice.

Witchcraft

The Quran and hadith both make reference to witchcraft and sorcery in the time of the Prophet Muhammad.23 Today, the survey finds, substantial numbers of Muslims continue to believe in the existence of witchcraft, although levels of belief vary widely across the countries included in the study, and – as discussed later in this report – very few Muslims believe the use of sorcery is an acceptable practice under Islam. (See Use of Sorcery in Chapter 6.)

In sub-Saharan Africa, the proportion of Muslims who say witchcraft or sorcery is real ranges from more than nine-in-ten in Tanzania (92%) to about one-in-six in Ethiopia (15%). A similar range of views is found in the Middle East and North Africa, where more than three-quarters of Muslims in Tunisia (89%) and Morocco (78%) believe in witchcraft, compared with as few as 16% in Egypt and 14% in the Palestinian territories.

Among the Southeast Asian countries surveyed, Indonesian Muslims are the most convinced that witchcraft is real (69%). In South Asia, Pakistani Muslims (50%) are more likely than their counterparts in Afghanistan (35%) or Bangladesh (9%) to believe in the existence of sorcery.

Meanwhile, in Southern and Eastern Europe, Albanian Muslims are the most likely to believe in witchcraft (43%), compared with a third or fewer elsewhere in the region.

Belief in the existence of witchcraft is least common in Central Asia. With the exception of Turkey, where about half of Muslims (49%) believe that sorcery exists, no more than three-in-ten in any of the Central Asian nations surveyed believe witchcraft is real.

Across most of the countries surveyed, Muslims who pray more than once a day are about as likely to accept the existence of witchcraft as those who pray less often. However, there are exceptions to this pattern. In Kosovo and Lebanon, Muslims who pray several times a day are significantly more likely to believe in sorcery (32 percentage points in the former, 16 points in the latter), while in Kyrgyzstan and Egypt the opposite is true: those who pray multiple times a day are slightly less likely to believe in witchcraft (by 10 and eight points, respectively).

Evil Eye

According to hadith, the Prophet Muhammad confirmed that the evil eye, borne by jealousy or envy, is real and capable of causing harm or misfortune.24 In 20 of the 39 countries surveyed, half or more Muslims say they believe in the evil eye.

Acceptance is generally highest in the Middle East and North Africa. With the exception of Lebanon (50%), solid majorities across the region affirm that the evil eye exists, including at least eight-in-ten Muslims in Tunisia (90%) and Morocco (80%).

Many Muslims in Central Asia also believe in the evil eye. Clear majorities in Turkey (69%) and Kazakhstan (66%) say the evil eye is real. About half in each of the other countries in the region share this view.

In Southern and Eastern Europe, Russian (59%) and Albanian (54%) Muslims are most likely to believe in the evil eye. Fewer say the same in Kosovo (40%) and Bosnia-Herzegovina (37%).

Opinion about the evil eye varies significantly across South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. In the former, Pakistani and Afghan Muslims are much more likely than their counterparts in Bangladesh to believe in the evil eye (61% and 53%, respectively, vs. 22%). Of countries surveyed in sub-Saharan Africa, Tanzania has the highest share of Muslims who say the evil eye is real (83%). In the majority of countries in the region, fewer than half accept that the evil eye exists.

In most nations surveyed, more believe the evil eye is real than say the same about witchcraft. Muslims in Southeast Asia, however, differ from this pattern. While 69% in Indonesia and 49% in Malaysia say witchcraft exists, just 29% and 36%, respectively, say the same about the evil eye.

Talismans

Some hadith condemn the wearing of talismans – charms or amulets bearing symbols or precious stones believed to have magical powers.25 In all countries surveyed a majority of Muslims report that they do not use magical objects to ward off evil or misfortune. Indeed, in 21 of 23 countries where the question was asked, fewer than three-in-ten Muslims say they wear talismans or precious stones for protection.

The practice of wearing talismans or amulets is most common among Pakistani and Albanian Muslims (41% and 39%, respectively). By comparison, in the remaining South Asian and Southern and Eastern European countries, roughly a quarter or fewer report wearing talismans.

Across Central Asia and the Middle East-North Africa region, only modest numbers rely on the protective powers of talismans or precious stones. In Central Asia, the wearing of talismans is most common in Kazakhstan (27%), Tajikistan (26%) and Turkey (23%). In the Middle East and North Africa, the practice is most common in Jordan (28%), Tunisia (25%) and Egypt (25%).

Overall, reliance on talismans is least common in Southeast Asia, where only a small number of Muslims in Indonesia (4%), Thailand (3%) and Malaysia (3%) report wearing objects to ward off evil or misfortune.

For the most part, there is little difference in the use of talismans between Muslims who pray several times a day and those who pray less often. One exception is in Lebanon, where those who pray more than once a day are 15 percentage points more likely to wear protective objects.

Smaller gaps by frequency of prayer are also found in Turkey (+13 percentage points among those who pray more than once a day) and Azerbaijan (+7). The opposite relationship is found in Tunisia (-12) and Morocco (-8), where those who pray less frequently are more likely to wear talismans.

Objects to Ward Off the Evil Eye

Although the survey finds that most Muslims do not wear talismans, a substantial number of Muslims appear to make an exception for charms kept at home to ward off the evil eye. In 14 of 23 countries where the question was asked, significantly more Muslims say they possess objects in their home to protect against the evil eye than say the same about wearing talismans.

The largest difference in the two practices is found in Azerbaijan, where Muslims are more than seven times as likely to have an object to protect against the evil eye as to wear talismans (74% vs. 10%). In the other Central Asian nations surveyed, the gaps are smaller, ranging from 27 percentage points in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan to nine points in Kyrgyzstan.

The use of charms to ward off the evil eye is also relatively common in some Middle Eastern and North African countries. Many more Muslims keep objects to protect against the evil eye than wear talismans in Iraq (+24 percentage points), Tunisia (+22), Lebanon (+17) and the Palestinian territories (+14).

In the other countries surveyed, the difference between the number of Muslims who use objects to ward off the evil eye and those who wear talismans tends to be small to negligible, although the gap is 18 percentage points in Afghanistan and 10 points in Russia.

In some countries, the use of objects to ward off the evil eye varies significantly by sect. In Azerbaijan, for example, 77% of Shia Muslims say they have items in their home to protect against the evil eye, compared with 57% of the country’s Sunni Muslims. Similarly, in Iraq, Shias are much more inclined than Sunnis to rely on charms against the evil eye, by a 56% to 28% margin. In Lebanon, however, there is no significant difference between Shias and Sunnis with respect to this practice.

In general, Muslims who pray several times a day are no more likely than less religiously committed Muslims to have objects to ward off the evil eye. But there are a few exceptions to this pattern, including Muslims in Azerbaijan (+23-percentage-point difference between Muslims who pray more than once a day and those who pray less often), Turkey (+19) and Lebanon (+13). In contrast, the reverse is true in Morocco (-17), Uzbekistan (-14) and Egypt (-14), with those who pray less often being more likely to have objects to ward off the evil eye.

Displaying Quranic Verses

In 19 of the 22 countries where the question was asked, it is more common for Muslims to display verses from the Quran in their home than it is to have talismans or objects to ward off the evil eye. In Southeast Asia, South Asia, and the Middle East and North Africa, seven-in-ten or more in all countries report having verses on display in their dwellings. This practice is somewhat less common in Central Asia and across Southern and Eastern Europe.

Overall, those who pray more than once a day are more likely to display Quranic writings in their home. This difference tends to be greatest in countries in Southern and Eastern Europe and in Central Asia, including Russia (+26 percentage points), Kyrgyzstan (+23), Turkey (+22), Azerbaijan (+19), Bosnia-Herzegovina (+18) and Tajikistan (+18).

Traditional Religious Healers

Substantial numbers of Muslims report that they turn to traditional religious healers when they or their family members are ill. This practice is common among Muslims in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. In the former region, more than half in Senegal (73%), Chad (68%), Cameroon (57%), Liberia (55%), Mali (55%) and Tanzania (53%) say they sometimes use traditional healers. In South Asia, most Afghan and Pakistani Muslims (66% and 55%, respectively) say the same.

Although a majority of Tajik Muslims (66%) also report turning to traditional religious healers, fewer in the other Central Asian nations say they sometimes seek such help for themselves or a family member.

Across the countries surveyed in Southeast Asia and the Middle East-North Africa region, fewer than half of Muslims say they ever enlist the aid of traditional religious healers. In Southeast Asia, the practice is most common in Thailand (48%), while in the Middle East and North Africa reliance on traditional healers is most prevalent among Muslims in Iraq (46%), Egypt (44%), Jordan (42%) and Tunisia (41%).

Muslims in Southern and Eastern Europe are less likely to consult traditional religious healers. About four-in-ten Albanian Muslims (38%) say they sometimes use such healers, while elsewhere in the region a quarter or fewer say they ever turn to a traditional healer.

In some countries, Muslims who pray several times a day are more likely than those who pray less often to use traditional religious healers. For example, in Jordan 47% of those who pray more than once a day have turned to traditional healers, compared with 31% of those who pray less often; in Turkey, the difference is 35% vs. 18%. Smaller but significant gaps are found in Kosovo (+16 percentage points among those who pray more than once a day), Azerbaijan (+15), Kyrgyzstan (+13), Egypt (+12) and Lebanon (+12).

Exorcism

The survey also asked respondents whether they have ever seen the devil or evil spirits being driven out of someone, as in an exorcism. Across Southern and Eastern Europe and in Central Asia fewer than one-in-ten Muslims say they have experienced or witnessed such an event. First-hand accounts are almost as rare in the Middle East and North Africa, although 18% of Moroccan Muslims say they have observed an exorcism. In South Asia and Southeast Asia, between 7% and 21% claim to have been present at an exorcism. Muslims residing in sub-Saharan Africa express greater familiarity with this practice: in 10 sub-Saharan countries, more than a quarter of all Muslims, including 48% in Ethiopia, say they have seen the devil or evil spirits being expelled from a person.

Footnotes:

22 The use of sorcery or witchcraft is condemned in the Quran (2:102), but some hadith indicate that certain types of spells or incantations (ruqyah) are permitted (Sahih Muslim 26:5448). With regard to the evil eye, certain hadith affirm that it is real (Sahih Muslim 26:5427; Sahih Muslim 26:5450), while some interpretations claim the Quran (68:51) also mentions the evil eye. Jinn are mentioned in the Quran (for example, 55:15; 55:56). (return to text)

23 See Quran 2:102; Sahih al-Bukhari 54:490. (return to text)

24 Sahih al-Bukhari 71:635; Sahih al-Bukhari 71:636. (return to text)

25 Sunan Abu Dawud 1:36. (return to text)

Photo Credit: © SZE FEI WONG / istockphoto