Because Hispanics are a relatively young population, they have had a major impact on U.S. school systems. Since 1980 the number of Hispanic children has nearly doubled, and the additional 4.5 million Latino children account for the bulk of the growth in the total number of children in the United States. There were 8.4 million Hispanic children enrolled in grades K-12 in 2001, accounting for 16% of all students. Their share is higher in the lower grades: 19% of students in kindergarten in 2001 were Latinos.

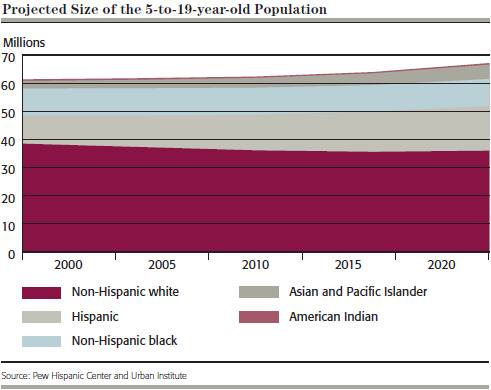

U.S. schools will continue to experience growing Hispanic enrollments for years to come. The Hispanic 5-to-19-year-old population is projected to grow from 11 million in 2005 to 16 million in 2020. By then Hispanics are projected to be 24% of the 5-to-19-year-old population. The second-largest minority group of youth — blacks — are not projected to grow, remaining at 10 million in number. Their share of the 5-to-19-year-old population is projected to fall to 14%.

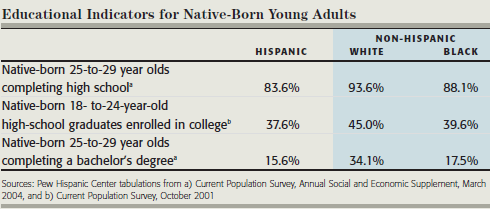

It is important to distinguish between native-born Hispanics and foreign-born Hispanics when analyzing educational achievement. More than 60% of Hispanic adults immigrated to the United States, and most of them did not attend U.S. schools because they arrived after age 18. But fewer than 20% of Hispanic students in grades K-12 immigrated to the United States, so the educational status of Latino youth is largely determined in U.S. schools. Looking at the whole Latino population, it is the least educated racial or ethnic group, with only American Indians and Alaskan Natives faring as poorly. For example, almost 90% of all young adults in the United States have finished high school, compared with only 62% of Latinos. While this is an important measure of the diminished social and economic prospects facing the Latino population, it is a poor indicator of what is happening in U.S. schools. Instead, that dramatic shortfall reflects the presence of many poorly educated adult immigrants. In contrast, 84% of native-born Hispanic young adults have finished high school, which is a better gauge of how Hispanic children are faring in U.S. schools.

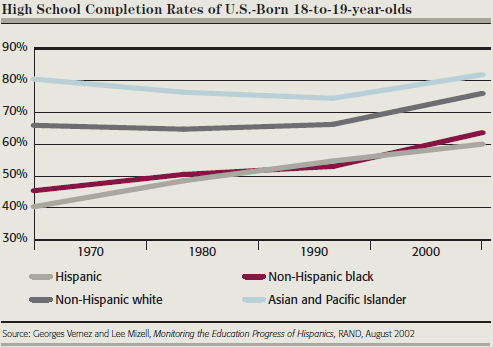

Finishing high school is a basic educational milestone, and here Latino children have made steady progress. In 1970, 40% of native-born Hispanic teens had finished high school. By 2000, the rate had improved significantly to 60% and the gap with white youth had narrowed. Similarly, Hispanic high school graduates go on to college at much higher rates than they did 30 years ago. Seventy percent of Latinos in the high school class of 1992 moved on to college, significantly higher than the 50% in the class of 1972.

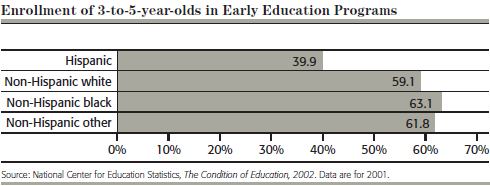

Nonetheless, there are large disparities between Hispanic and white students across the educational spectrum. Differences in early learning set the stage for later problems. Before the onset of formal schooling, Hispanic children are significantly less likely than other children to attend preschool programs. In 2001, 40% of Hispanic children 3 to 5 years old enrolled in early childhood education programs, compared with about 60% of other children.

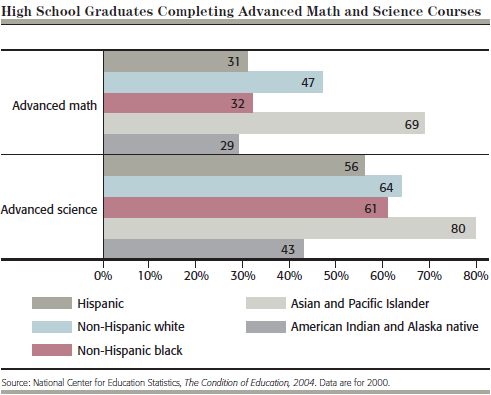

At the high school level, while many Latino youths graduate, their course work in mathematics, science and English is less advanced than that of their white classmates. For example, 31% of Hispanic high school graduates and 47% of white students complete at least one math course more challenging than Algebra II and Geometry I. This difference in high school learning contributes to the differences in what white and Hispanic youths accomplish when they go on to college.

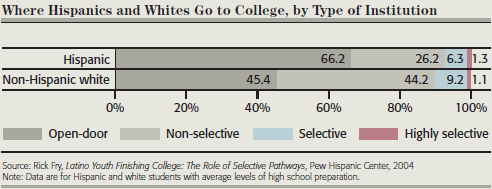

Latino college students do not attend the same kinds of institutions as do white undergraduates. Latinos are more likely to attend community colleges and the four-year colleges they attend are more likely to be less-selective institutions. This disparity in college outcomes partly reflects differences in high school preparation, but other factors are also involved. Even comparing Hispanic college freshmen with white freshmen who have an average or near-average level of high school preparation in terms of coursework, the Hispanic freshmen tend to attend less selective colleges or universities. One plausible explanation is economic. Tuition is less expensive at community colleges and many less selective public four-year colleges; students can study while living at home; and course schedules accommodate students who must work full time as they go to college.

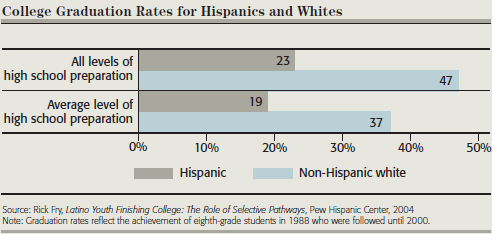

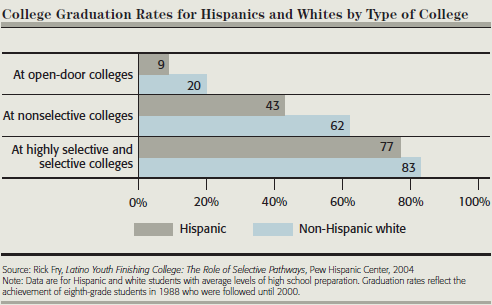

Hispanic undergraduates are much less likely to finish college than white undergraduates. Almost half of all young white post-secondary entrants finish a bachelor’s degree, in comparison with fewer than a quarter of all young Hispanic post-secondary entrants. This critical difference can partly be accounted for by high school preparation and college-entry differences. But even similarly prepared Hispanic and white students have very different graduation rates. Looking only at students who left high school with an average level of preparation, whites were twice as likely as Latinos to graduate from college — 37% versus 19%. And these differences persist for similarly prepared entrants within similar colleges. For example, among Hispanic four-year college entrants with an average or near-average level of high school preparation attending nonselective colleges, 43% completed a bachelor’s degree. Similarly prepared white entrants at nonselective institutions graduated at a 62% rate.

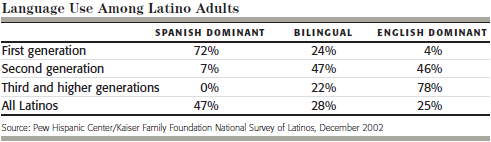

Spanish is the dominant language of the Hispanic adult population because of the presence of immigrants. Even so, more than a quarter of the foreign-born population speaks some English. The language profile is very different among native-born Latinos. Nearly half of the second generation only speaks English and the other half is almost all bilingual, meaning they can speak and read both languages. Virtually all Latinos whose parents were born in the United States speak English and none are Spanish dominant.

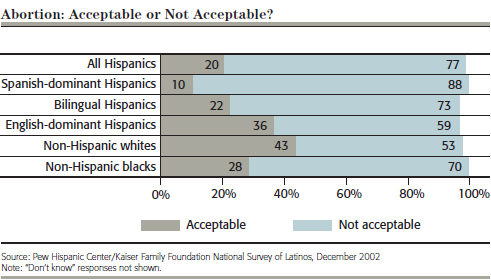

The Pew/Kaiser surveys have found that Spanish-dominant Latinos — those who have little or no mastery of English and who primarily rely on Spanish in their home and work lives — have strikingly different opinions about controversial social issues such as abortion, divorce and homosexuality. For example, only 10% of Spanish-dominant Latinos say they find abortion acceptable, compared with 36% of English-dominant Hispanics. On this issue, as on questions about divorce and homosexuality, the English-dominant Latinos have views that are closer to those of whites than to those of Spanish-dominant Latinos.