Large majorities in most of the 19 countries surveyed have negative views of China, but relatively few say bilateral relations are bad

This Pew Research Center analysis focuses on public opinion of China in 19 countries in North America, Europe, the Middle East and the Asia-Pacific region. Views of China, its president, its bilateral relations and its policies on human rights are examined in the context of long-term trend data.

For non-U.S. data, the report draws on nationally representative surveys of 20,944 adults from Feb. 14 to June 3, 2022. All surveys were conducted over the phone with adults in Canada, Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Japan, Malaysia, Singapore and South Korea. Surveys were conducted face to face in Hungary, Poland and Israel and online in Australia.

In the United States, we surveyed 3,581 U.S. adults from March 21 to 27, 2022. Everyone who took part in the U.S. survey is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

Due to the coronavirus outbreak, face-to-face interviewing is not currently possible in many parts of the world. For this study, we conducted surveys only in places where nationally representative telephone or online surveys are feasible, or where vaccination rates and outbreak rates were at sufficiently safe levels that our local contractors believed face-to-face interviewing could be safely conducted. Opinion of China may differ in other countries where we are not currently able to survey and we hope to be able to resume this work in a broader group of countries in upcoming years.

Here are the questions used for the report, along with responses, and the survey methodology.

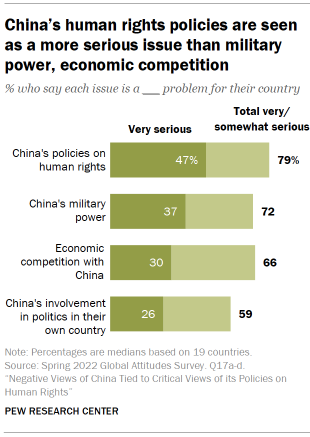

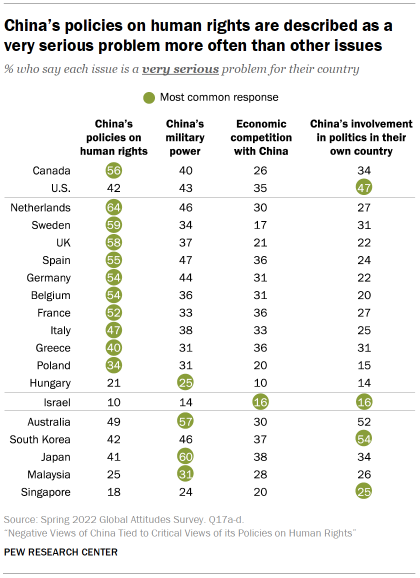

Negative views of China remain at or near historic highs in many of the 19 countries in a new Pew Research Center survey. Unfavorable opinions of the country are related to concerns about China’s policies on human rights. Across the nations surveyed, a median of 79% consider these policies a serious problem, and 47% say they are a very serious problem. Among the four issues asked about – also including China’s military power, economic competition with China and China’s involvement in domestic politics in each country – more people label the human rights policies as a very serious problem than say the same of the others.

Unfavorable views are also closely related to concerns about China’s military power – something that a median of 37% say is a very serious problem. Worries are particularly acute among China’s neighbors – especially Japan (60%), Australia (57%) and South Korea (46%) – though nearly half in some non-geographically proximate countries like Spain (47%) and the Netherlands (46%) also feel this way.

Economic competition with China is seen as a less serious problem. A median of 30% describe it as very serious, and outside of Israel, it is not seen as the top problem among the four tested in any of the 19 countries.

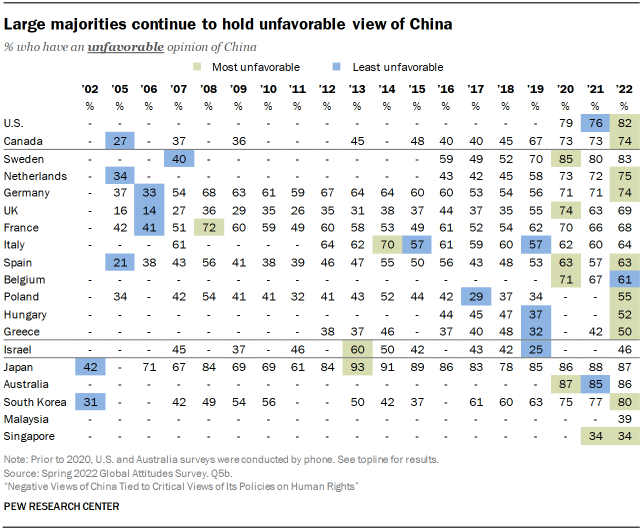

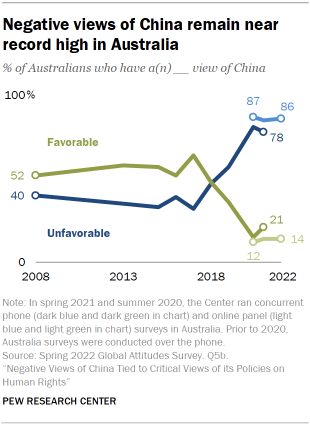

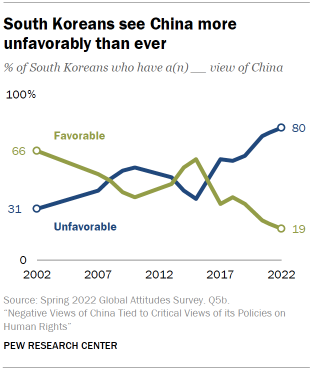

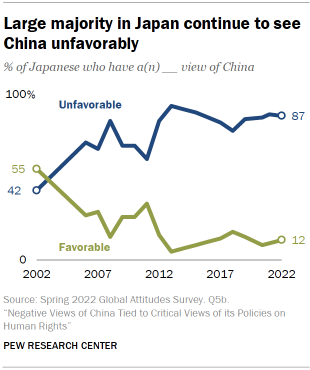

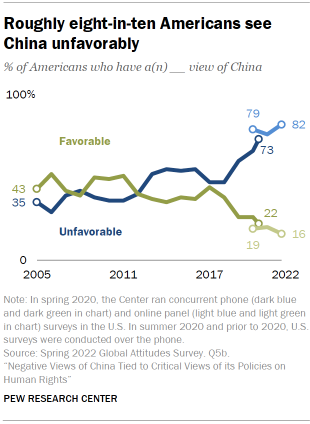

Negative views of China shot up in 2020 in many of the places surveyed; since then, they have largely remained near these elevated levels or even increased. Today, unfavorable opinion of China is at or near historic highs in most of the 18 countries for which trend data is available.

Adults in Greece, the United Kingdom and the United States have become significantly more critical of China over the past year. Unfavorable views of China have gone up by 21 percentage points in Poland and Israel and 15 points in Hungary, which were all last surveyed in 2019. Belgium stands as the only country where fewer people hold an unfavorable view of China this year than last year (61%, down from 67%).

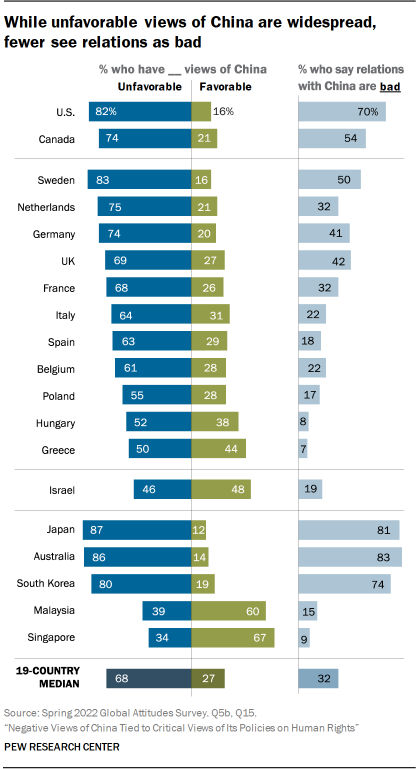

Despite broadly unfavorable opinions about China, majorities in over half of the countries surveyed think relations between their country and the superpower are currently in good shape. Take, for example, the Netherlands: 75% have negative views of China, and the country – which was the first in Europe to pass a motion declaring treatment of the Uyghurs in China to be a genocide – stands apart for having the highest share (64%) calling China’s policies on human rights a very serious problem. Still, 65% of the Dutch people think their country’s relationship with China is currently in good shape.

The countries where bilateral relations are seen negatively tend to be those where another problem is paramount: China’s involvement in domestic politics. While a median of only 26% describe this issue as very serious, it is seen as particularly severe in places like South Korea, Australia, the U.S. and Japan – the four places where a majority says relations are in bad shape.

Spotlight: Views of China in countries where bilateral relations are strained

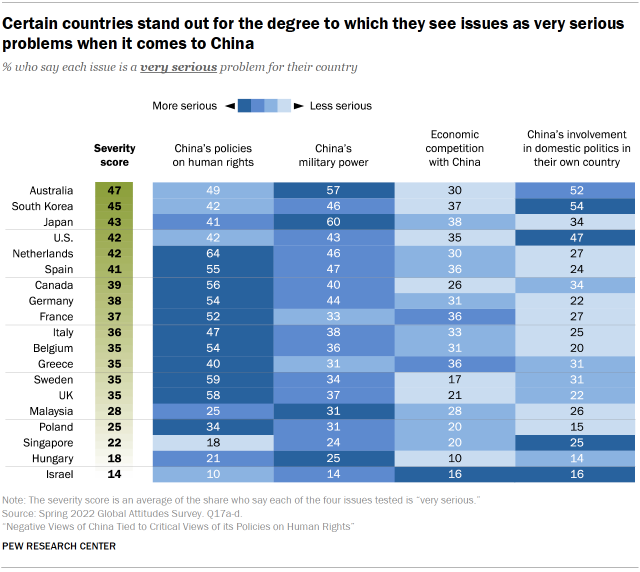

One way to explore views of China is to look at which publics are most concerned about all of the four issues tested: China’s policies on human rights, China’s military power, economic competition with China and China’s involvement in politics in each country. Taking the average of the share in each country who says each issue is “very” serious creates a “severity score”. The “severity score” is highly correlated with both unfavorable views of China (r=+0.81) and the sense that bilateral relations are poor (r=0.72). Four countries stand out for having high scores on this measure and for saying relations with China are bad: Australia, South Korea, Japan and the U.S.

Australia

Australian views of China turned particularly negative in phone surveys conducted between 2019 and 2020 but have stayed consistently negative since then, with 86% reporting unfavorable views this year. More Australians (83%) describe bilateral relations with China as bad than do the same in any of the other countries surveyed. Australians score highest when it comes to seeing each of the four problems asked about as very serious problems for their country. They also stand out for the degree to which they view China’s military power as a very serious issue (57%). The survey was conducted a few weeks after a high-profile incident involving Chinese ships but prior to the interception of an Australian aircraft.

South Korea

South Korea was heavily affected by Chinese economic retribution following the country’s 2017 decision to install an American missile interceptor (THAAD). Negative views of China went up substantially in 2017 alongside this turmoil; they increased again in 2020 when, in the wake of COVID-19, unfavorable opinion went up in nearly every country surveyed. But views have continued to sour and today, and unfavorable views of China are at a historic high of 80%. Around three-quarters of Koreans think bilateral relations with China are in poor shape, and the country stands out for having the highest share of people (54%) who say that China’s involvement in domestic politics is a very serious problem for the country. South Korea is also the only country surveyed where young people have more unfavorable views of China than older people.

Japan

For the past 20 years, Japanese views of China have always been among the most negative in our surveys, if not the most negative, and this year is no exception: 87% have an unfavorable view of China. This is only slightly lower than the historic high of 93% who had an unfavorable view of China in 2013, following extreme tension in the East China Sea. Very unfavorable views of China have also been particularly elevated since 2020, with around half of Japanese adults saying this describes their views of China. Compared with other publics, a greater share in Japan say that China’s military power is a very serious problem for their country (60%) and that relations with China are poor (81%).

United States

Negative views of China have fluctuated over time in the U.S., but there has been a consistent upward trajectory since 2018. Today, 82% of Americans have an unfavorable view of China, up slightly (+6 percentage points) since last year and now hovering near historic highs. Seven-in-ten Americans also describe current bilateral relations with China as poor. Republicans in the U.S. are somewhat more likely than Democrats to have negative views of China and to describe relations as poor.

These are among the major findings of a new Pew Research Center survey, conducted from Feb. 14 to June 3, 2022, among 24,525 adults in 19 nations. Other key findings include:

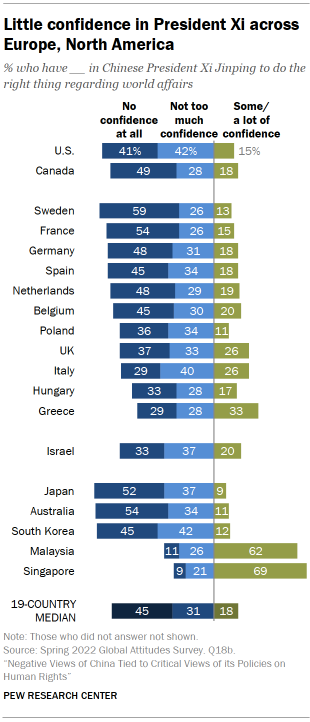

- Few have confidence in Chinese President Xi Jinping to do the right thing regarding world affairs. Outside of Singapore and Malaysia, a majority say they have little or no confidence in him, including at least three-quarters who say this in Japan (89%), Australia (88%), South Korea (87%), Sweden (85%), the U.S. (83%), France (80%), Germany (79%), Spain (79%), Canada (77%), the Netherlands (77%) and Belgium (75%). In most places, negative views of Xi did not significantly change over the past year and continue to hover at or near historic highs. (For more on attitudes toward Xi, U.S. President Joe Biden, Russian President Vladimir Putin and other world leaders, see “International Attitudes Toward the U.S., NATO and Russia in a Time of Crisis.”)

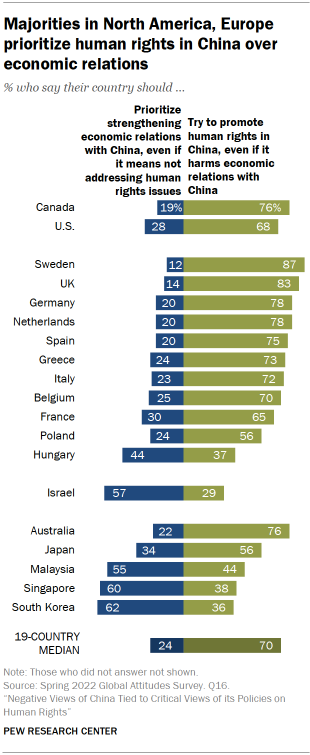

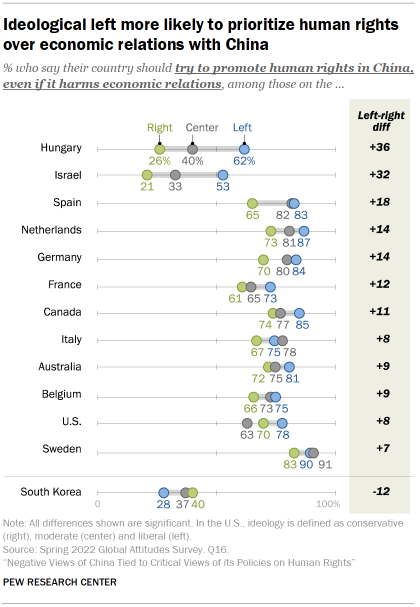

- Across most places surveyed, a majority of people think it is more important to try to promote human rights in China, even if it harms economic relations with China, rather than prioritizing strengthening economic relations with China, even if it means not addressing human rights issues. However, there are clear regional differences: In the U.S., Canada and every European country surveyed except Hungary, majorities say human rights should be prioritized over economic relations. In Israel and most places surveyed in the Asia-Pacific region, the opposite is true; majorities in Malaysia, Singapore and South Korea favor strengthening their economic relationships with China, even if it means not addressing human rights issues. Those on the ideological left are particularly likely to favor promoting human rights compared with those on the ideological right.

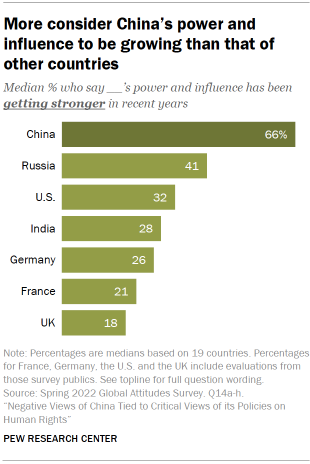

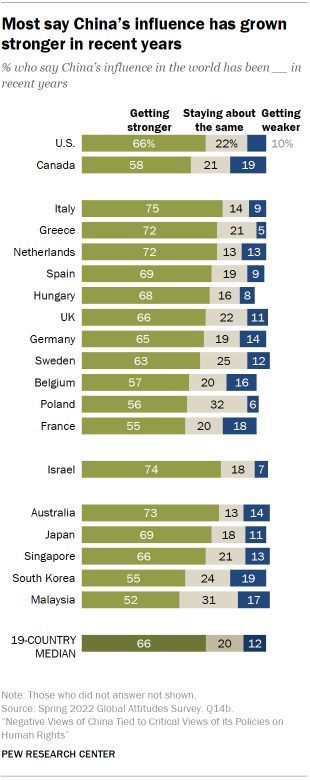

- Half or more in every country surveyed think China’s influence in the world has gotten stronger in recent years, as opposed to getting weaker or staying about the same. This is many more than say the same of other countries asked about, including Russia, the U.S., India, Germany, France and the UK. In most countries, people who say economic competition with China is a very serious problem for their country are more likely to say China’s influence in recent years has strengthened. (For more on how views of China’s power and influence compare with that of the U.S., see “Across 19 countries, more people see the U.S. than China favorably – but more see Chinese influence growing.”)

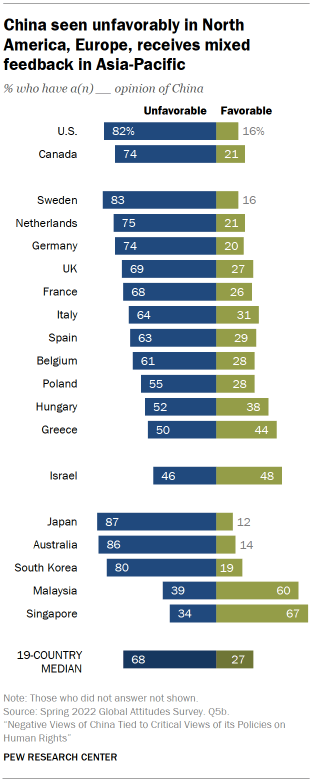

Views of China mostly negative with some exceptions

Across the 19 countries surveyed, a median of 68% say they have an unfavorable view of China. In North America, about three-quarters or more see China unfavorably, including more than a third in both the U.S. and Canada who hold a very unfavorable opinion of China.

Majorities in nine of the 11 European countries surveyed also hold unfavorable views of China. Those in Sweden, the Netherlands and Germany are particularly negative: About three-quarters or more say their opinion of China is unfavorable. Roughly two-thirds in the UK and France agree. Views in Greece are more divided, with 50% saying they have an unfavorable view and 44% holding a favorable view.

Opinions in Israel are also divided, with roughly equal shares holding unfavorable and favorable views (46% vs. 48%).

Views vary most widely across the five Asia-Pacific countries surveyed. In Japan, Australia and South Korea, at least eight-in-ten hold unfavorable views of China. This includes 47% in Japan, 43% in Australia and 32% in South Korea who have a very unfavorable opinion of the country. Malaysians and Singaporeans see China differently. Six-in-ten or more in both countries say they hold a favorable opinion of China. In both countries, those who identify as ethnically Chinese are more likely than those who identify as another ethnicity to hold favorable views of China.

Adults in Greece, the U.S. and the UK have become significantly more critical of China over the past year. And unfavorable views of China have gone up by 21 percentage points in Poland and Israel and by 15 points in Hungary, which were all last surveyed in 2019. In the U.S., South Korea, the Netherlands, Germany, Canada, Spain, Poland, Hungary and Greece, unfavorable views of China are also at the highest level recorded since the Center started polling on this issue. Belgium stands as the only country where fewer people hold an unfavorable view of China this year than last (61%, down from 67%).

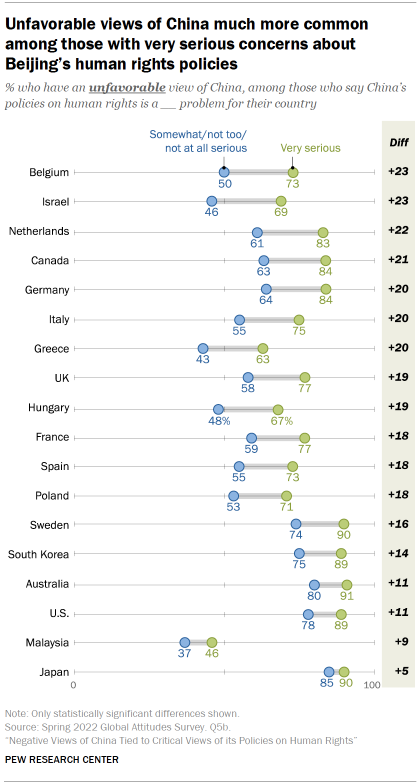

Unfavorable views of China are, in part, linked to concerns about the country’s policies on human rights. In 18 of 19 countries surveyed, those who say China’s human rights policies are a very serious problem for their country are significantly more likely than those who are less concerned to hold an unfavorable view of China. The difference is greatest in Belgium, where 73% of those who say China’s policies on human rights are a very serious problem see China unfavorably and 50% of those who consider Beijing’s human rights policies a less serious problem say the same. Singapore is the only country where there is no significant difference.

Reservations about China’s military power and involvement in their country’s politics also tie into how people see China. Those who say China’s military power is a very serious problem for their country are more inclined to see China unfavorably in most countries. Only in South Korea and Greece are people equally likely to hold unfavorable views of China regardless of how they view its military power. Similarly, those who consider China’s involvement in their country’s politics a very serious problem are more likely to hold an unfavorable view of China in all countries except the Netherlands, Japan and Malaysia. The idea that economic competition from China is a very serious problem is likewise related to more negative views in most countries.

In some countries, older adults are more likely to hold an unfavorable view of China. For example, in Japan, 90% of adults ages 50 and older say they have an unfavorable view of China, which is 18 points higher than the 72% of adults ages 18 to 29 who say the same. The opposite is true in South Korea: Adults under 30 are 22 points more likely than those 50 and older to hold an unfavorable view of China.

China’s policies on human rights are seen as a very serious problem by many

People across the 19 countries surveyed see myriad issues in their country’s bilateral relationship with China. When it comes to the four issues asked about – China’s military power, economic competition with China, China’s policies on human rights and China’s involvement in domestic politics – large majorities in most countries tend to describe each as at least a somewhat serious problem.

When it comes to which problem is seen as most serious, however, China’s policies on human rights stands out. A median of 47% describe the issue as very serious, ranging from a high of 64% who say this in the Netherlands to a low of 10% who say the same in Israel. Europeans are much more likely to describe China’s policies on human rights as a very serious problem than those in the Asia-Pacific: Outside of Greece (40%), Poland (34%) and Hungary (21%), around half or more in every European country hold this view, while Australia is the only Asia-Pacific nation where this view is similarly prevalent.

In contrast, China’s military power – which is seen as a very serious threat by a median of 37% – is seen as a relatively more important problem in the Asia-Pacific region. In every Asia-Pacific country surveyed, more people describe China’s military power as a very serious problem for their country than say the same about Beijing’s human rights policies, while the opposite is true in every European country surveyed except Hungary. Japan and Australia particularly stand out for having publics where a majority is very concerned about China’s military.

A median of 30% describe economic competition with China as a very serious problem. Opinion is relatively similar across most places surveyed, ranging from a high of 38% in Japan to a low of 10% in Hungary, with around three-in-ten in most places saying this is a very serious issue.

While fewer in most places describe China’s involvement in politics in their country as a very serious problem, it is the top concern in South Korea (54%), the U.S. (47%) and Singapore (24%). Around half in Australia (52%) also describe this as a very serious problem.

There are very few differences between men and women or among those who have higher and lower levels of education when it comes to concerns about China. In some countries, older people tend to be somewhat more concerned – particularly regarding China’s military power. For example, 55% of those ages 65 and older in South Korea say China’s military power is a very serious problem, compared with 31% of those under 30. These age dynamics are especially pronounced in the U.S., where older people are more likely to call every issue asked about a very serious problem for the U.S.

Those on the ideological left in some countries are more likely to say China’s policies on human rights are a very serious problem. In Israel, for example, those on the left (27%) are more than five times as likely as those on the right (5%) to say the issue is very serious. On the other hand, those on the ideological right tend to be relatively more concerned about economic competition with China.

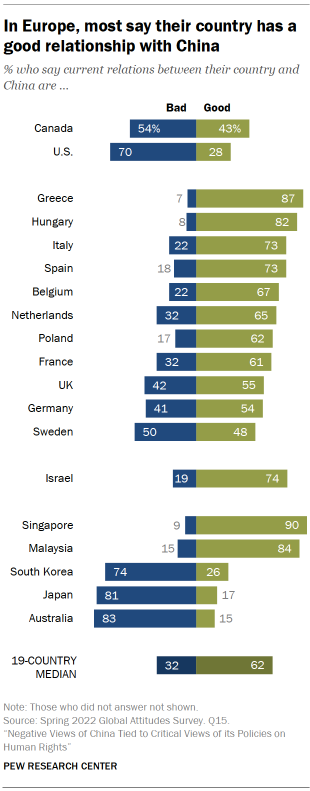

Evaluations of bilateral relations with China vary widely

When asked to evaluate their country’s relationship with China, most say the relationship is good, though results vary widely across regions. A median of 62% across the 19 countries surveyed say current relations between their country and China are good, and a median of 32% say relations are bad.

More than half in Canada and the U.S. say their country’s relationship with China is bad. This includes about one-in-ten in both countries who say the relationship is very bad.

In Europe, the feedback is more positive. About nine-in-ten in Greece and two-thirds or more in Hungary, Italy, Spain and Belgium say current relations between their country and China are good. Majorities in the Netherlands, Poland, France and the UK also share this perspective. Views in Sweden are mixed: Roughly equal shares offer positive and negative evaluations of the relationship.

Israelis have a positive outlook on bilateral relations with China: About three-quarters say the relationship is good, and roughly one-in-ten say the relationship is very good.

Opinions in the Asia-Pacific region vary widely. In both Singapore and Malaysia, more than eight-in-ten say relations between their country and China are good. This includes about a quarter in both countries who say the relationship is very good. On the other hand, about three-quarters or more in South Korea, Japan and Australia describe bilateral relations with China as bad. In all three countries, at least about a fifth say relations are very bad.

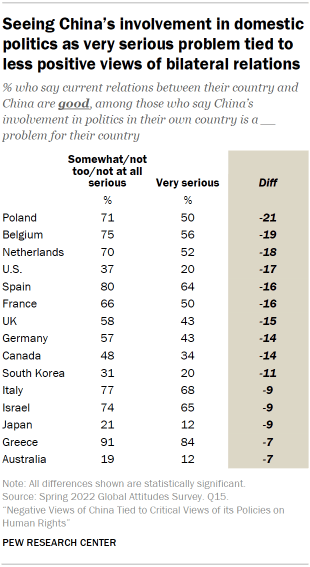

How people see specific issues in their country’s bilateral relationship with China is linked to overall evaluations of the relationship. In 15 of 19 countries, those who see China’s involvement in their country’s politics as a very serious problem are less likely than those who show less concern to describe the bilateral relationship as good. For example, 50% of Poles who say China’s involvement in Polish politics is a very serious problem say China and Poland have a good relationship. Conversely, 71% of Poles who see China’s influence in politics as a less serious problem consider the relationship good.

Serious concerns about China’s human rights policies are also tied to less optimism about the bilateral relationship in 15 countries. And those who are very troubled by China’s military power or economic competition from China are less inclined to describe the bilateral relationship as good in 14 and 13 countries, respectively.

Most favor promoting human rights over strengthening economic ties with China

When asked to choose between promoting human rights in China and strengthening economic ties with China – both potentially at the expense of the other – clear regional differences emerge. In the U.S., Canada and nearly all of the European countries surveyed, majorities say human rights should be prioritized over economic relations. In Israel, the opposite is true. Opinion in the Asia-Pacific is divided: Majorities in Malaysia, Singapore and South Korea favor strengthening their economic relationships with China, even if it means not addressing human rights issues.

In nearly all places surveyed, those who see China’s human rights policies as a very serious problem favor promoting human rights regardless of economic consequences. For example, 87% of Canadians who see China’s policies as a very serious issue prioritize human rights, compared with 64% of those who show less concern. This is the case in each country surveyed except Malaysia.

Preference for promoting human rights or strengthening economic ties is also related to ideology. In 12 of the 19 countries surveyed, people on the ideological left choose promoting human rights over strengthening economic ties with China. The opposite is true only in South Korea, where 72% of those on the left favor strengthening economic ties even if it means not addressing human rights issues, compared with 58% of those on the right. In the U.S., while those on the ideological left (“liberals” in U.S. parlance) are more likely to hold this view than those on the right (“conservatives”), they are also both more likely to think this than those in the center (“moderates”). (For more on U.S. opinion toward China, see “China’s Partnership With Russia Seen as Serious Problem for the U.S.”)

Although few people in most of the countries surveyed say they have a favorable view of China, those that do are far more likely to prioritize economic relations over human rights. In Australia, 45% of those who see China favorably place economic relations ahead of human rights in regard to China, compared with just 18% of those who hold unfavorable views of the country.

Many think China’s international influence is getting stronger

A median of 66% across the 19 countries surveyed say China’s influence in the world has been getting stronger – as opposed to getting weaker or staying about the same – in recent years. This is more than say the same of India or Russia, two other emerging economies asked about in the survey, and of the U.S., Germany, France or the UK.

In the U.S. and Canada, about six-in-ten or more say China’s influence is growing stronger and roughly a fifth say the country’s influence is staying about the same.

Europeans agree that China’s influence in recent years has been getting stronger. Three-quarters in Italy say China’s influence is growing, as do at least two-thirds in Greece, the Netherlands, Spain and Hungary. Substantial minorities in the European countries surveyed also say that China’s influence is staying about the same, ranging from about a third in Poland (32%) to about a tenth in the Netherlands (13%).

Most Israelis say China’s influence is growing stronger. About three-quarters say the country’s influence is getting stronger, and about a fifth say the influence is staying about the same.

Pluralities in the Asia-Pacific countries surveyed agree that China’s influence is growing. In Australia, Japan and Singapore, about two-thirds or more hold this view, and about half or more in South Korea and Malaysia agree. In both Malaysia and Singapore, those who self-identify as ethnically Chinese are more inclined to say China’s influence is getting stronger than those who identify as another race or ethnicity.

Education, income and gender are tied to how people evaluate China’s influence in recent years. In 14 countries, those with more education are more likely than those with less schooling to say China’s influence is growing stronger. The same pattern holds for those with higher incomes and men, when compared with those with lower incomes and women. In some countries, those with more education, those with higher incomes and men are also more likely to provide an answer to the question.

Few have confidence in Chinese President Xi Jinping

Majorities in all countries surveyed – except Singapore and Malaysia – have little to no confidence in Chinese President Xi Jinping’s approach to world affairs. Around four-in-ten or more in most places surveyed even say they have no confidence at all in Xi, including more than half of those in Australia, France and Sweden.

Roughly seven-in-ten adults or more have little or no confidence in Xi in the U.S., Canada and all but two of the European countries surveyed. In Greece, while more still say they distrust than trust Xi (57% vs. 33%, respectively), opinion is somewhat more divided.

The Asia-Pacific region is very divided. While Japan, Australia and South Korea are among the publics with the least confidence in Xi, Malaysia and Singapore stand out for the opposite: A majority has at least some confidence in the Chinese leader.

Confidence in Xi is closely related to views of China at large. In all places surveyed, people with favorable views of China are more likely to have confidence in the president than those who see China unfavorably.

In Malaysia and Singapore, confidence in Xi differs by ethnic identity. In both countries, adults who describe themselves as ethnic Chinese have more confidence in Xi than those who identify as Malay or another ethnicity.