Large ideological divides persist on views of tradition, national pride and discrimination, especially in the U.S.

This report focuses on attitudes in the U.S., France, Germany and the UK about what it takes to be truly part of the country’s nationality. It also includes questions about the importance of tradition and national pride, among other issues.

For this analysis, we use data from nationally representative telephone surveys of 4,069 adults from Nov. 10 to Dec. 23, 2020, in the U.S., France, Germany and the UK. In addition to the survey, Pew Research Center conducted focus groups from Aug. 19 to Nov. 20, 2019, in cities across the U.S. and UK (see here for more information about how the groups were conducted). We draw upon these discussions in this report.

Here are the questions used for the report, along with responses, and the survey methodology.

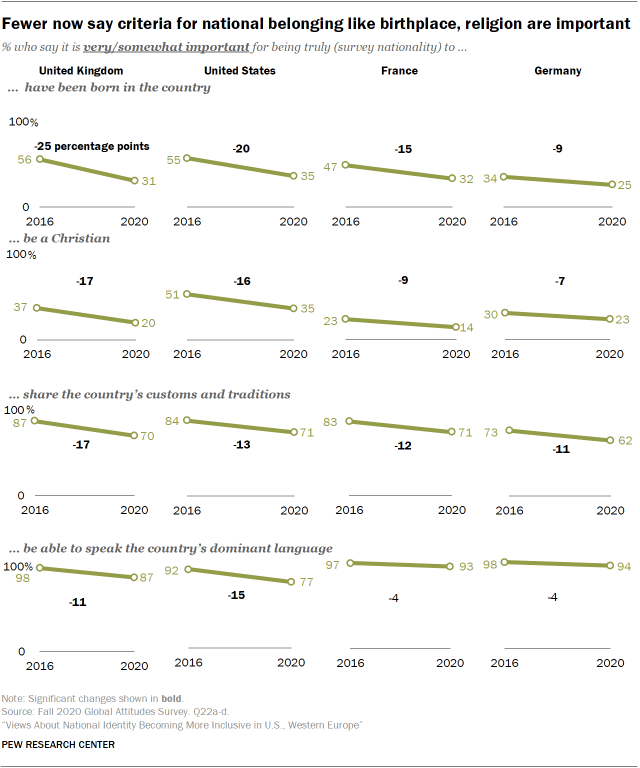

As issues about culture and identity continue to be at the center of heated political debates in the United States and Europe, a new Pew Research Center survey finds that views about national identity in the U.S., France, Germany and the UK have become less restrictive and more inclusive in recent years. Compared with 2016 – when a wave of immigration to Europe and Donald Trump’s presidential campaign in the U.S. made immigration and diversity a major issue on both sides of the Atlantic – fewer now believe that to truly be American, French, German or British, a person must be born in the country, must be a Christian, has to embrace national customs, or has to speak the dominant language.

People in all four nations have also become more likely to believe that immigrants want to adopt the customs and ways of life in their countries. Nearly two-thirds of Americans (65%) now hold this opinion, up from 54% in 2018, and the share of the public expressing this view in Germany has jumped from 33% to 51% over the same time period.

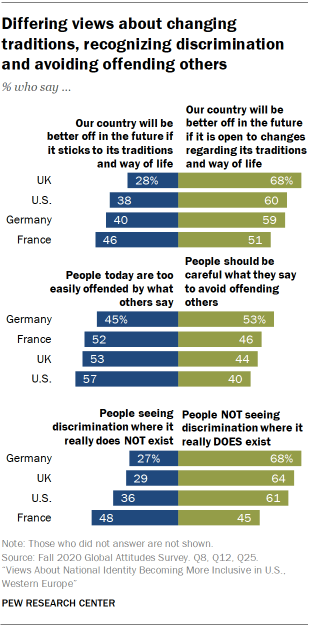

The survey also finds that more people think their countries will be better off in the future if they are open to changes regarding traditional ways of life. Still, this issue is divisive, as a substantial minority in every country prefer to stick to traditions.

Other cultural issues also divide these publics. For example, when it comes to issues of “political correctness,” at least four-in-ten in every country say people should be careful what they say to avoid offending others – even while around half or more in every country but Germany say people today are too easily offended by what others say.

Outside of France, more people say it’s a bigger problem for their country today to not see discrimination where it really does exist than for people to see discrimination where it really is not present.

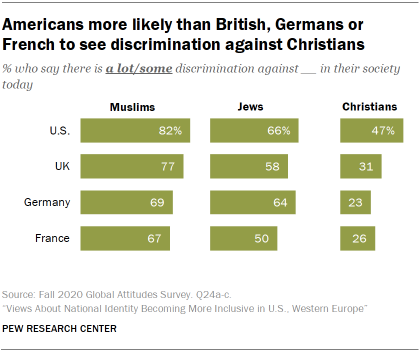

Depending on the country, people are also divided over which groups are facing discrimination in society today. In the U.S., for example, nearly half say Christians face at least some discrimination, though fewer than a third say the same in the European countries surveyed. Similarly, in France, the public is somewhat evenly divided over whether Jews face discrimination. In every country surveyed, though, a large majority think Muslims face discrimination.

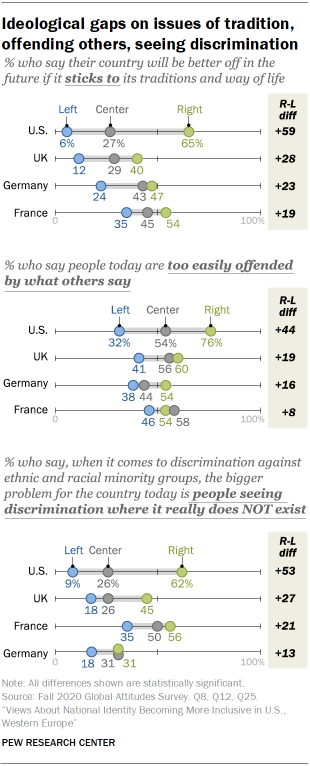

All of these issues are also ideologically divisive.1 In every country surveyed, those on the right are more likely than those on the left to prioritize sticking to traditions, to say people today are too easily offended by what others say, and to say the bigger societal problem is seeing discrimination where it does not exist.

Those on the right are also more likely to say each factor asked about – being born in the country, adopting its customs and traditions, speaking the dominant language and being Christian – are very important for being part of the citizenry.

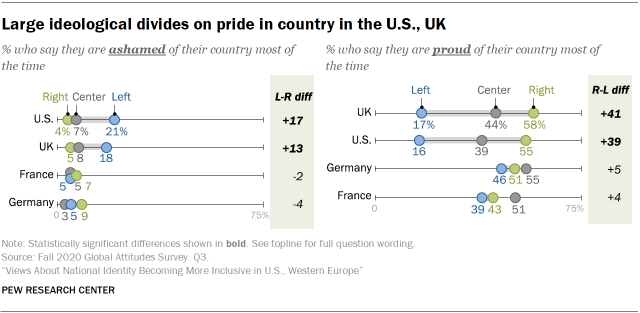

Even issues of national pride have become ideologically tinged in the U.S. and UK. In every country, around four-in-ten say they are proud of their country most of the time, one-in-ten or fewer say they are ashamed of their country most of the time, and the balance say they are both proud and ashamed. But, while those on the left and right are equally likely to say they are proud most of the time in both France and Germany, in the U.S. and UK, those on the right are more than three times as likely to say they are proud most of the time than those on the left (or conservatives are about three times as likely to say they are proud most of the time than liberals, in American parlance). In these two countries, those on the left are equally likely to describe themselves as ashamed most of the time as to say they tend to be proud.

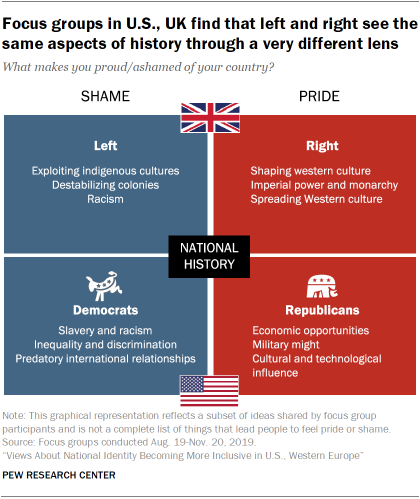

Focus groups conducted in the U.S. and UK during the fall of 2019 shed light on which issues were points of pride and shame for Americans and Britons in their countries, respectively. Most notably, issues of pride for some were often sources of shame for others. In the UK, one such issue was the concept of empire. Those on the ideological right praised the historic empire for its role in spreading English and Western culture overseas, while those on the ideological left discussed how the UK had disrupted local cultures and often left chaos in its wake in its former colonies.

“Why would you be ashamed of history?”

–Woman, 55, Birmingham, Right Remainer

“Although it’s an impressive feat to expand the empire as far as it went, that came with quite a lot of shameful things.”

–Man, 34, Newcastle, Right Leaver

In the U.S., too, whereas groups composed of Republicans discussed American history through the lens of opportunity, groups composed of Democrats stressed the inadequacy of how American history is taught – and how it often glosses over racism and inequitable treatment of minority groups. Republican participants, for their part, even brought up how political correctness itself makes them embarrassed to be American – while Democratic participants cited increased diversity as a point of pride.

Themes of pride and shame were also present in focus group discussions in these two countries regarding what it means to be British or American, respectively. These conversations revealed that national identities are changing, driven in part by globalization and multiculturalism. Quotations from the focus groups appear throughout this report to provide context for the survey findings. They do not represent the opinion of all Americans or Britons on any given topic. They have been edited lightly for grammar and clarity.

Pew Research Center conducted 26 focus groups from Aug. 19 to Nov. 20, 2019, in cities across the U.S. and UK (for details on how the groups were stratified, see the methodology). All groups followed a discussion guide designed by Pew Research Center and were asked questions about their local communities, national identities and globalization by a trained moderator.

This report draws from those discussions, and we have included quotations which have been lightly edited for grammar and clarity. Quotations are chosen to provide context for the survey findings and do not necessarily represent the majority opinion in any particular group or country.

“I think [America] was better [in the past], pre-cancel culture, which is the weaponization of difference, basically … Now that politics is so divided, to be blunt, the left, myself included, have just been like no, if you are not living up to my ideals, I don’t need to interact with you. I think it has become problematic and that is why you have this polarity and extremism.”

–Man, 34, Seattle, Democrat

While Britons are as ideologically divided as Americans on issues of pride, when it comes to every other cultural issue asked about in this report, Americans stand out for being more ideologically divided than those in the Western European countries surveyed. For example, on whether the country will be better off in the future if it sticks to its traditions and way of life, the gap between the left and right in the U.S. is 59 percentage points – more than twice the gap found in any other country (the UK is the next most divided country, at 28 points). The ideological divide in the U.S. is also around two times larger than that in any other country when it comes to whether people today are too easily offended by what others say (a 44-point liberal-conservative gap in the U.S.) and whether it is a bigger problem for the country today that people see discrimination where it does not exist (a 53-point liberal-conservative gap).

The ideological gap between liberals and conservatives has also widened in recent years over what it takes to be truly American. While liberals and conservatives are equally less likely today to say being Christian is important for being truly American compared to the past, on each of the other criteria asked about, liberals have shifted significantly more than conservatives. For example, 54% of liberals now say it’s important to speak English to be truly American, down from 86% who said the same in 2016. But among conservatives, 91% say it’s important to speak English, largely unchanged from the previous 97%. Still, conservative opinions have shifted markedly on the issue of whether it’s important to have been born in the U.S. and whether immigrants want to adopt the country’s customs. For more on how the U.S. stands out ideologically, see “Ideological divisions over cultural issues are far wider in the U.S. than in the UK, France and Germany.”

These are among the findings of a new Pew Research Center survey conducted from Nov. 10 to Dec. 23, 2020, among 4,069 adults in the France, Germany, the UK and the U.S. This report also includes findings from 26 focus groups conducted in 2019 in the U.S. and UK. In addition to ideological divisions, the survey also finds that cultural attitudes split along other dimensions including age, populist party support and religion. For example:

- Younger people – those under 30 – are less likely to place requirements on Christianity, language, birth or adopting the country’s traditions to be part of their country than older age groups. They are also more likely to say their country will be better off if it is open to changes. The notable exception to this pattern is Germany, where opinion differs little by age.

- Supporters of right-wing populist parties are less likely to see discrimination against Muslims in their society. They are also more likely to say birthplace, adherence to national traditions and customs and being Christian is key to belonging in their country, as well as to prioritize tradition over change.

- Christians are more likely to say there is a great deal of discrimination against Christians in their society than against non-Christians. They are also more likely to say that being Christian is essential to truly being part of their country’s citizenry. But they are also more likely to say other key factors – including speaking the language and being born in the country – are essential components of national belonging. On other issues, too, they stand apart from non-Christians. For example, they tend to be more likely to say they are proud of their country and to favor sticking to traditions and customs.