Six-in-ten Americans believe scientists should play an active role in policy debates over issues related to their expertise. But the public’s views divide along party lines, according to a new Pew Research Center survey.

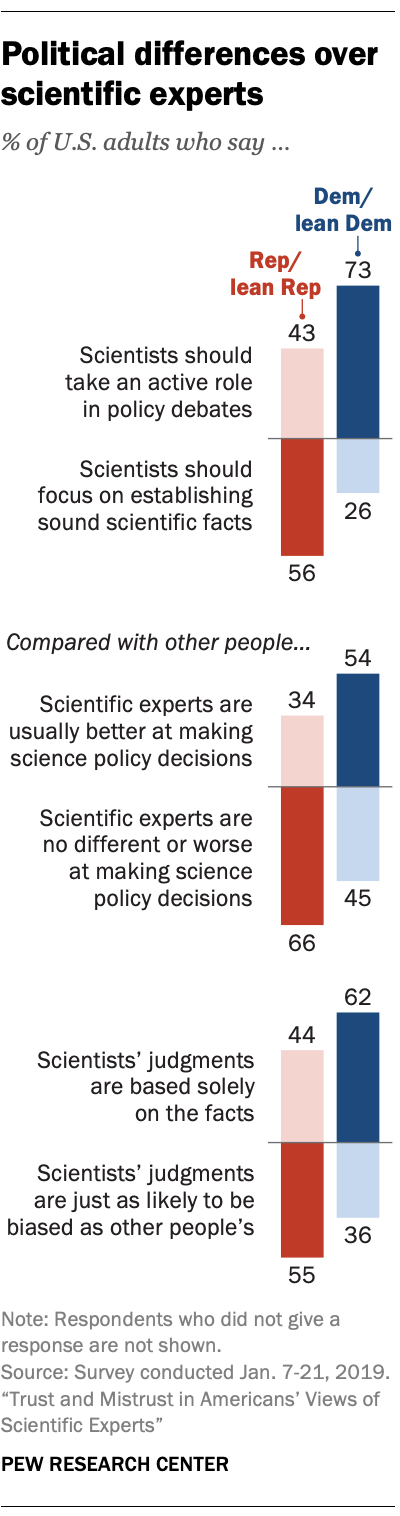

Most Democrats and independents who lean to the Democratic Party (73%) think scientists should take an active role in policy debates. In contrast, a majority of Republicans and Republican leaners (56%) say scientists should stay out of policy debates and instead focus on establishing sound scientific facts.

Most Democrats and independents who lean to the Democratic Party (73%) think scientists should take an active role in policy debates. In contrast, a majority of Republicans and Republican leaners (56%) say scientists should stay out of policy debates and instead focus on establishing sound scientific facts.

Democrats put more faith in scientists’ judgments than Republicans do. For example, 54% of Democrats say policy decisions from scientific experts are usually better than other people’s. Republicans are less convinced: Two-thirds say scientists’ policy decisions are either worse than or no different from those of other people. And while a majority of Democrats (62%) say scientists’ judgments are based solely on the facts, fewer than half of Republicans (44%) say this. Instead, a majority of Republicans (55%) think scientists’ judgments are just as subject to bias as anyone else’s judgments.

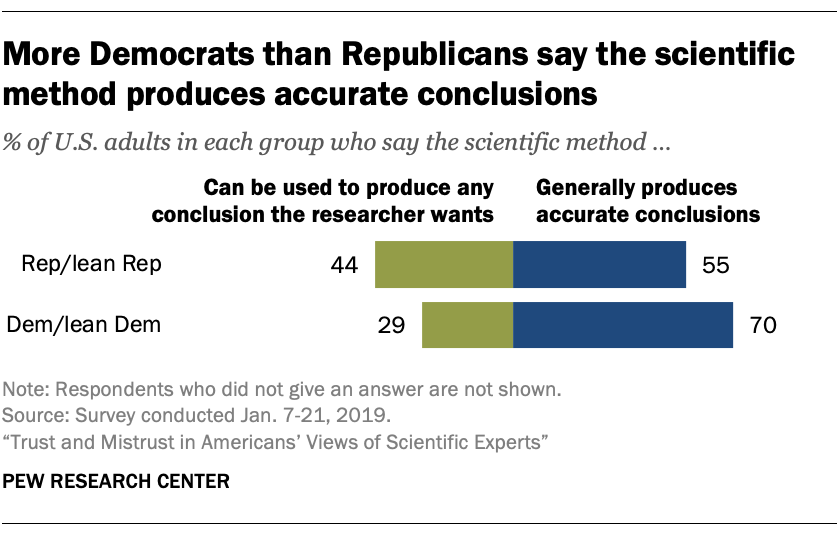

Overall, a 63% majority of Americans say the scientific method generally produces sound conclusions. But, here too, Democrats have more confidence than Republicans. Seven-in-ten Democrats see the scientific method as generally sound. A smaller majority of Republicans (55%) say the same, while 44% believe the scientific method can be used to produce any conclusion the researcher wants.

Overall, a 63% majority of Americans say the scientific method generally produces sound conclusions. But, here too, Democrats have more confidence than Republicans. Seven-in-ten Democrats see the scientific method as generally sound. A smaller majority of Republicans (55%) say the same, while 44% believe the scientific method can be used to produce any conclusion the researcher wants.

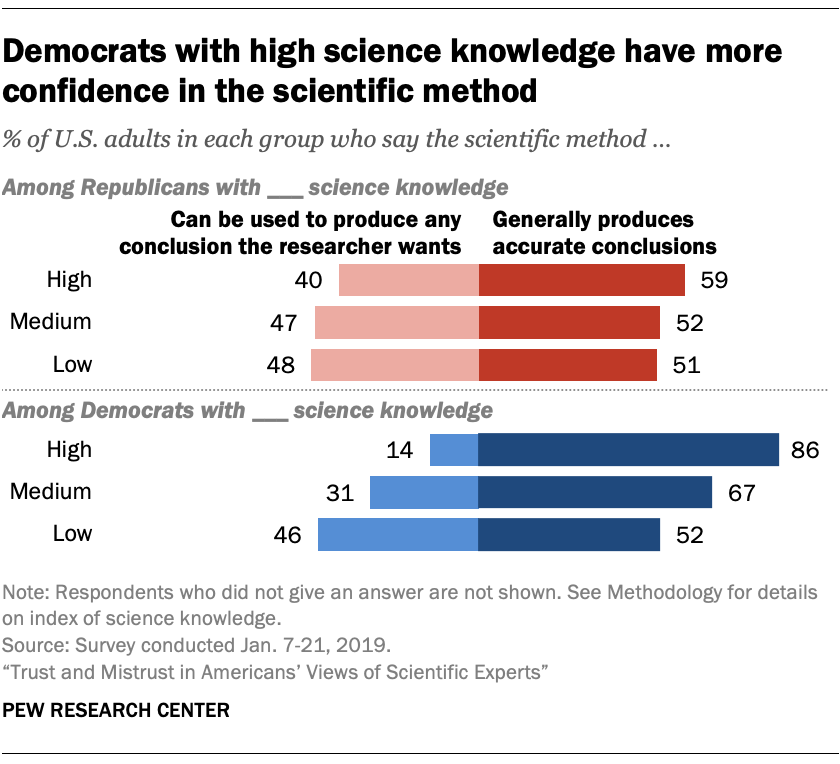

There’s a common supposition in the scientific community that people who know and understand more about science should hold more positive views about it. But the data from the Center’s survey points to a more complicated story.

While Americans’ factual knowledge about science is associated with their views about scientific experts, the effect depends on their partisan lens.

Two examples illustrate this pattern. Democrats with a high degree of science knowledge are much more likely than those with low science knowledge to say the scientific method generally produces accurate conclusions (86% vs. 52%). Among Republicans, however, there are only modest differences by science knowledge on this question.

Two examples illustrate this pattern. Democrats with a high degree of science knowledge are much more likely than those with low science knowledge to say the scientific method generally produces accurate conclusions (86% vs. 52%). Among Republicans, however, there are only modest differences by science knowledge on this question.

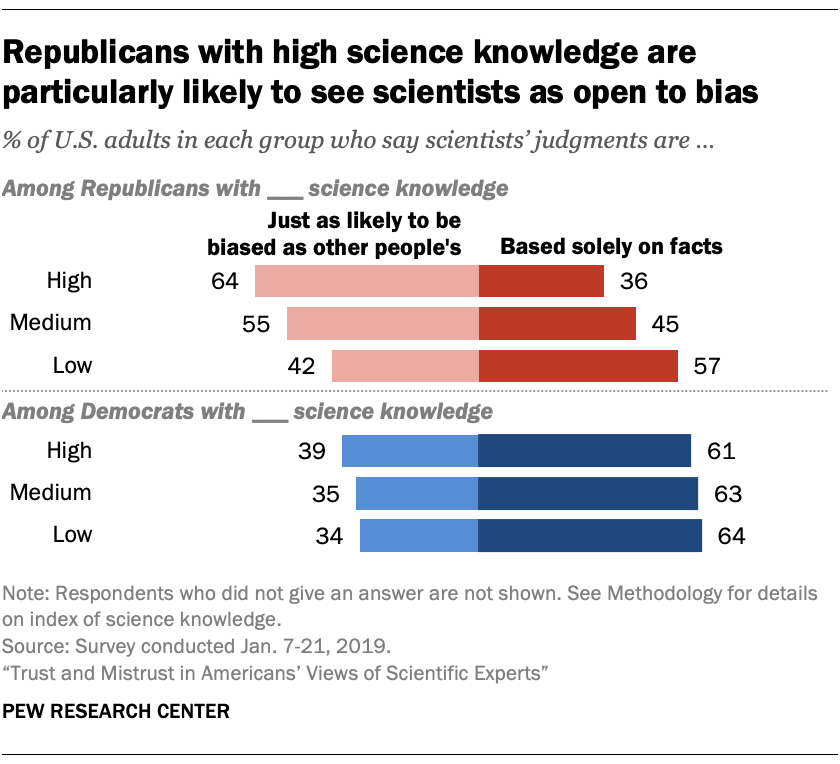

The pattern plays out in reverse when it comes to the perceived susceptibility of scientists to bias. Roughly two-thirds of Republicans with high science knowledge (64%) say scientists are just as likely to be biased as other people, compared with 42% of those with low science knowledge. In contrast, Democrats with low, medium and high science knowledge are all about equally likely to think scientists are susceptible to bias (34% to 39%).

The pattern plays out in reverse when it comes to the perceived susceptibility of scientists to bias. Roughly two-thirds of Republicans with high science knowledge (64%) say scientists are just as likely to be biased as other people, compared with 42% of those with low science knowledge. In contrast, Democrats with low, medium and high science knowledge are all about equally likely to think scientists are susceptible to bias (34% to 39%).

Past Pew Research Center surveys have found similar patterns in public views about climate and energy issues.

Note: See the Methodology section of the main report for more information on the index of science knowledge.