Share of Latinos who are religiously unaffiliated continues to grow

For this analysis, we surveyed 7,647 U.S. adults, including 3,029 Hispanics, from Aug. 1-14, 2022. This includes 1,407 Hispanic adults on Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP) and 1,622 Hispanic adults on Ipsos’ KnowledgePanel. Respondents on both panels are recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. Recruiting panelists by phone or mail ensures that nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. This gives us confidence that any sample can represent the whole population, or in this case the whole U.S. Hispanic population. (Refer to our “Methods 101” explainer on random sampling for more details.)

To further ensure the survey reflects a balanced cross-section of the nation’s Hispanic adults, the data is weighted to match the U.S. Hispanic adult population by age, gender, education, nativity, Hispanic origin group and other demographic categories, based on the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2019 American Community Survey. The data is also weighted to match the Hispanic adult population by religious affiliation, party affiliation, and frequency of internet use, based on Pew Research Center’s 2021 National Public Opinion Reference Survey.

“Hispanic” and “Latino” are used interchangeably in this report.

The term “U.S. born” refers to people who are U.S. citizens at birth, including people born in the 50 U.S. states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico or other U.S. territories, as well as those born elsewhere to at least one parent who is a U.S. citizen.

“Foreign born” refers to persons born outside of the United States to parents who were not U.S. citizens. The terms “foreign born” and “immigrant” are used interchangeably in this report.

Language dominance is a composite measure based on self-described assessments of speaking and reading abilities. Spanish-dominant people are more proficient in Spanish than in English (i.e., they speak and read Spanish “very well” or “pretty well” but rate their English-speaking and reading ability lower). Bilingual refers to people who are proficient in both English and Spanish. English-dominant people are more proficient in English than in Spanish.

“Democrats and Democratic leaners” refers to respondents who identify politically with the Democratic Party or who identify politically as independent or with some other party but lean toward the Democratic Party. “Republicans and Republican leaners” refers to respondents who identify politically with the Republican Party or who identify politically as independent or with some other party but lean toward the Republican Party.

Evangelical Protestant refers to respondents who identify as Protestant or as Jehovah’s Witnesses and say they consider themselves born-again or evangelical Christians. Non-evangelical Protestant refers to Protestants or Jehovah’s Witnesses who say they are not born-again or evangelical Christians, or who decline to answer the question about born-again or evangelical status. The small number of Protestants who were not asked if they consider themselves born-again or evangelical Christians are not included in either group.

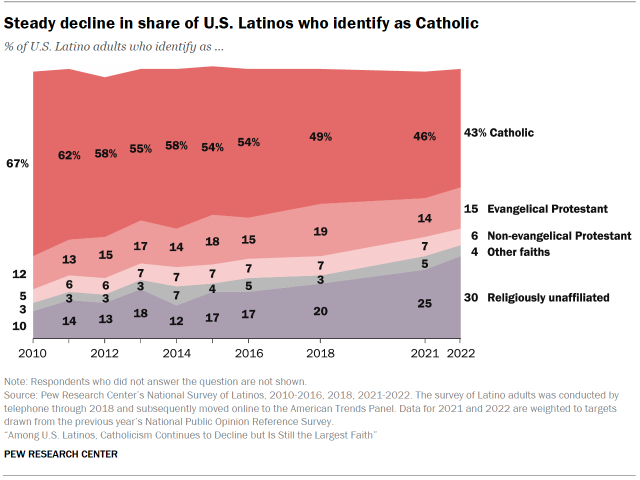

Catholics remain the largest religious group among Latinos in the United States, even as their share among Latino adults has steadily declined over the past decade, according to a new analysis of Pew Research Center surveys. By contrast, the share of Latinos who identify as Protestants – including evangelical Protestants – has been relatively stable, while the percentage who are religiously unaffiliated has grown substantially over the same period.

As of 2022, 43% of Hispanic adults identify as Catholic, down from 67% in 2010. Even so, Latinos remain about twice as likely as U.S. adults overall to identify as Catholic, and considerably less likely to be Protestant. Meanwhile, the share of Latinos who are religiously unaffiliated (describing themselves as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular”) now stands at 30%, up from 10% in 2010 and from 18% a decade ago in 2013. The share of Latinos who are religiously unaffiliated is on par with U.S. adults overall.

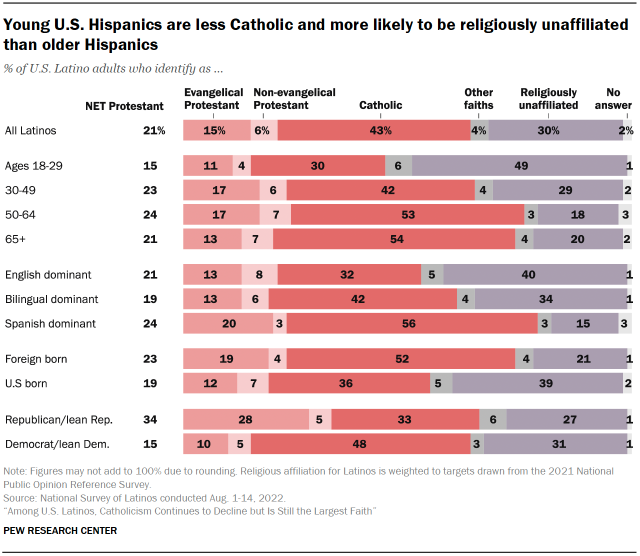

The demographic forces shaping the nation’s Latino population also have impacted religious affiliation trends. Young people born in the U.S. – not immigrants – have driven Latino population growth since the 2000s. Among U.S. Latinos ages 18 to 29, 79% were born in the United States.1 About half (49%) of Latinos in this age group now identify as religiously unaffiliated. By contrast, only about one-in-five Latinos ages 50 and older are unaffiliated; most of these older Latinos (56%) were born outside the U.S.2 Overall, 52% of Latino immigrants identify as Catholic and 21% are unaffiliated. U.S.-born Latinos are less likely to be Catholic (36%) and more likely to be unaffiliated (39%), according to a 2022 Pew Research Center survey of Latino adults.

Protestants are the second-largest faith group after Catholics, accounting for 21% of Hispanic adults, a share that has been relatively stable since 2010. During this time, Hispanic Protestants consistently have been more likely to identify as evangelical or born again than to say they are not born again or evangelical.

As of 2022, 15% of Latinos are evangelical Protestants, a share that has remained relatively stable over the past decade. Latino evangelicals have received national attention recently due to the political activism of some evangelical churches. The interest in Latino evangelicals comes as White evangelicals have become a bulwark of support for Republican candidates in U.S. presidential elections, and after elections in which a rising share of Latino voters have supported Republican candidates.

About three-in-ten Hispanic Republicans (28%) identify as evangelical Protestants, a far higher share than the 10% of Hispanic Democrats who say the same. Latino immigrants also are somewhat more likely than U.S.-born Latinos to be evangelical (19% vs. 12%). Evangelicalism is especially prevalent among Latinos with Central American origins, mirroring a pattern seen in those countries. Roughly three-in-ten U.S. Latinos with Central American origins (31%) say they are evangelical Protestants, a higher share than among those with roots in Puerto Rico (15%) and Mexico (12%).

Looked at in the opposite direction, among evangelical Protestants who are Latino, half identify with the Republican Party or are independents who lean toward the GOP, and 44% are Democrats or Democratic-leaning independents. Among Latino Catholics, by contrast, fewer (21%) are Republicans, while 72% identify as Democrats. Religiously unaffiliated Latinos are also heavily Democratic (66% Democratic vs. 24% Republican).

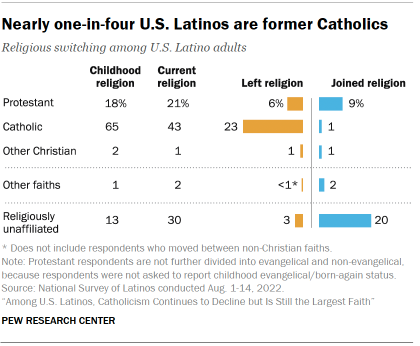

Childhood religion and religious switching among Latinos

Another way of measuring religious change is to ask respondents how they were raised, religiously, and see how that compares with their current religious identity.

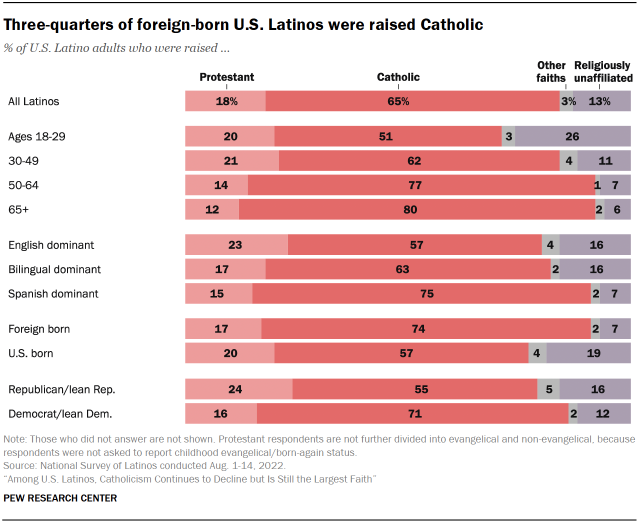

Most U.S. Latinos (65%) say they were raised Catholic, while far fewer say they were raised Protestant (18%), religiously unaffiliated (13%) or in some other religion (3%). Older Latinos and those who were born outside the U.S. are especially likely to say they were raised Catholic.

But like Americans overall, many Latinos switch away from their childhood religion. As of 2022, one-third of Latino adults indicate that their current religion is different from their childhood religion.

Catholicism has seen the greatest losses due to religious switching among Hispanics. Nearly a quarter of all U.S. Hispanics are former Catholics: While about two-thirds of Hispanic adults (65%) say they were raised Catholic, 43% say they are currently Catholic, according to the 2022 survey. And for every 23 Latinos who have left the Catholic Church, only one has converted to Catholicism.

By contrast, the religiously unaffiliated have experienced the biggest gains. Fewer Latinos say they were raised with no religious affiliation (13%) than currently identify as unaffiliated (30%). For every Latino raised without a religious affiliation who has joined a religion in adulthood (totaling 3% of all Latino adults), about seven Latinos have left their childhood religion and become unaffiliated (20%).

Protestantism has seen more modest growth due to religious switching among Latinos. For every two Latinos who were raised as Protestants before converting to another faith or becoming unaffiliated, about three have converted to Protestantism in adulthood. In all, 18% of U.S. Latinos say they were raised Protestant, while 21% say they are currently Protestant.

Catholicism has seen similarly large losses among both U.S.-born and foreign-born Hispanics. About one-in-five U.S.-born Hispanics (22%) were raised Catholic and no longer identify as Catholic; this is the case for 23% of foreign-born Hispanics. Disaffiliation from religion is somewhat more common among U.S.-born Hispanics: About a quarter of U.S.-born Hispanics (23%) say they were raised in a faith but are now religiously unaffiliated, compared with 16% of foreign-born Hispanics.

U.S.-born Hispanics are about as likely to become Protestants as to leave Protestantism (7% vs. 8%). But among foreign-born Hispanics, 4% were raised Protestant but have since left the religion, compared with 11% who were raised in another tradition (or no religion) and have since become Protestants.

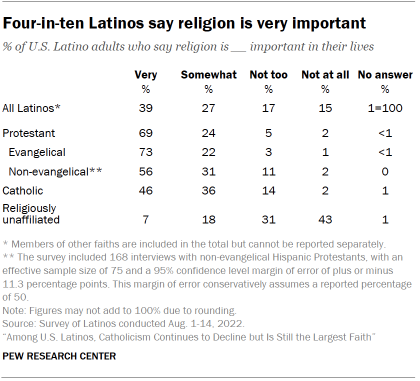

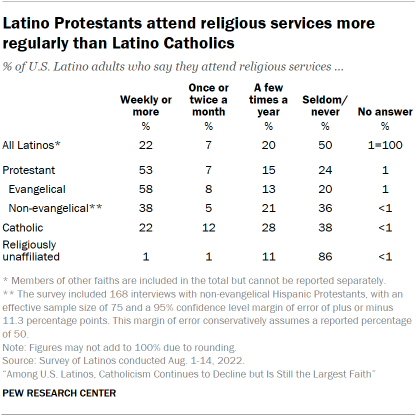

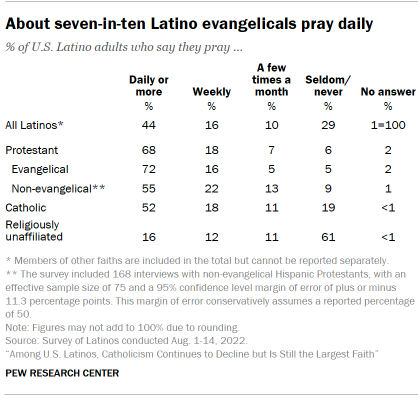

Religious commitment among U.S. Latinos

Religious commitment among Latinos falls along a spectrum. Protestants are especially likely to say religion is important to them and to report that they frequently pray and attend religious services. At the other end of the spectrum are the unaffiliated, sometimes called religious “nones,” who are a relatively nonreligious group. Catholics fall somewhere in the middle.

Hispanic evangelical Protestants express especially high levels of religious commitment; nearly three-quarters (73%) say religion is very importantto them. Non-evangelical Protestant (56%) and Catholic (46%) Hispanics are somewhat less likely to say this. And about three-quarters of unaffiliated Hispanics say religion is not too or not at all important in their lives.

Similarly, nearly six-in-ten Latino evangelicals (58%) say they attend religious services weekly or more often, compared with 37% of non-evangelical Protestants and 22% of Catholics. (A similar share of U.S. Catholics overall, 26%, say they attend Mass weekly.) The vast majority of religiously unaffiliated Americans seldom or never attend services, including 86% of unaffiliated Latinos.

Most Latino evangelicals also say they pray daily (72%), while non-evangelical Protestants are about as likely as Catholics to do this (55% and 52%, respectively). Most Latino “nones” seldom or never pray (61%), though a substantial minority (29%) say they pray at least weekly.

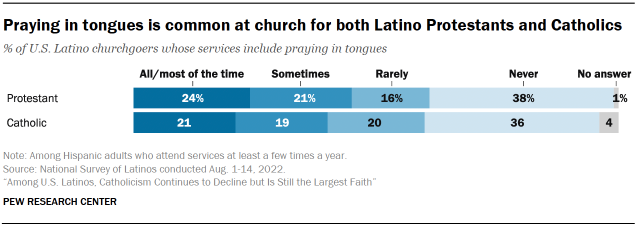

Many U.S. Latinos attend services where people pray in tongues

Pentecostalism and other forms of charismatic Christianity have grown in influence in Latin America. A distinguishing characteristic of Pentecostalism is its emphasis on spirit-filled forms of worship, such as speaking in tongues.

Nearly half of U.S. Hispanic Protestant churchgoers (45%) say their services include praying in tongues at least sometimes. The share is even higher among Hispanic Protestants who describe themselves as evangelical or born-again Christians (57%). Attending services where people pray in tongues is much less common among churchgoing U.S. Protestants overall (27%).3

Four-in-ten Mass-attending Latino Catholics also say their services at least sometimes involve praying in tongues, compared with about a quarter (24%) of U.S. Catholic churchgoers overall, according to a previous analysis.