As newspapers employ fewer statehouse reporters, nonprofits are filling much of the void

Pew Research Center conducted this study to provide data on the number of journalists covering state capitols across the U.S., updating and adding to a 2014 study on the same topic. Center researchers spent roughly six months reaching out to editors, reporters and other news media employees; legislative and gubernatorial press secretaries; and other experts on state government to gather as complete as possible an accounting of the nation’s statehouse reporting pool. The study breaks down the number of statehouse reporters by state and media sector and also examines how they correlate with each state’s population and legislative session length.

The study is made up of three components: a census of reporters covering statehouses, conducted with the goal of being as complete as possible; a set of 24 qualitative interviews with statehouse reporters and other stakeholders on their experiences in the field and the changes they have seen; and a study on reporters covering tribal governments in Native American communities, including eight additional interviews.

For the census of reporters, researchers compiled a list of news outlets covering state issues from several different industry sources and the original 2014 study, and then sent invitations to journalists working at those outlets to participate in an intake questionnaire. The questionnaire asked respondents about statehouse reporting at their outlet, while also asking them to identify other outlets that may have statehouse reporters. In addition, researchers followed up (by email and phone) with 1) outlets identified by other statehouse reporters working in the same state, 2) outlets included in the state’s press association list, and 3) outlets that were identified by legislative and press staff at the state’s capitol. Researchers verified the information for each outlet included in the study, though this accounting ultimately relies on self-reported data and responses. Data was collected between Sept. 23, 2021, and March 11, 2022. Since this time period, staffing may have shifted due to the commencement or ending of legislative sessions and/or newsroom layoffs, departures, restructuring or hiring.

The 24 interviewees familiar with statehouse reporting were selected nonrandomly from contacts who responded to the study, as well as other political stakeholders and other industry experts. The interviewees were selected to represent a range of states, outlet types and outlet sizes, among other variables. Each interview was conducted by a senior writer with a journalism background and typically took between 20 and 30 minutes.

The data on coverage of tribal governments was gathered through outreach to contacts identified from various sources as having experience at outlets covering Native American communities, and additional in-depth interviews with eight people.

For more details, see the Methodology.

This report was funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts, with generous support from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation and Arnold Ventures. It is the latest report in Pew Research Center’s ongoing investigation of the state of news, information and journalism in the digital age, a research program funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts, with generous support from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.

CORRECTION (Oct. 27, 2023): This report has been corrected throughout to reflect new information, received in August 2023, that reduced the number of student statehouse reporters in Nebraska from 40 to three. While many figures in the report were changed in the process, including in graphics and tables, the new information does not affect the substantive conclusions of the study. For questions, please email Pew Research Center.

From voting rights and redistricting to abortion and public education, state capitols across the United States are at the epicenter of the nation’s key public policy debates. This has been especially true during the COVID-19 pandemic, as state capitol buildings became ground zero in the debate over mask and vaccine mandates and other pandemic policies.

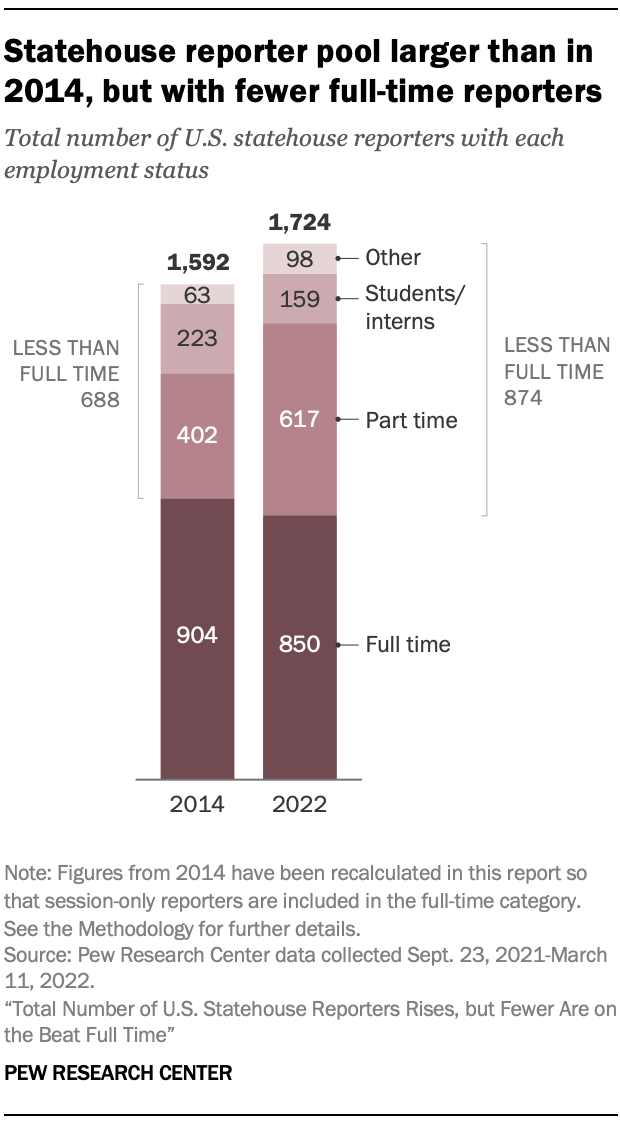

A new Pew Research Center study finds that the total number of reporters assigned to the 50 state capitols to inform citizens about legislative and administrative activity has increased by 8% since 2014, the last time this study was conducted. The gain comes largely from two main developments: new nonprofit news outlets that are employing statehouse reporters, and a shift to more part-time statehouse reporting.

Indeed, although the total number of statehouse reporters has increased, fewer reporters are now covering state governments full time. Out of the 1,724 statehouse reporters identified by this study, just under half (850, or 49%) report on the statehouse full time. This means that they are assigned to the state’s capitol building to cover the news there on a full-time basis – either year-round or during the legislative session – reporting on everything from legislative activity to the governor’s office to individual state agencies. Being fully devoted to this coverage often provides the greatest opportunity to engage with the statehouse and produce stories that go beyond the basic contours of daily news. The remaining 874 statehouse reporters either cover the beat part time, are students/interns (whether at a university-run news service or at another news outlet) or are other supporting staff.

This is a notable change from 2014, when more than half of statehouse reporters were covering state government on a full-time basis. The total number of full-time statehouse reporters nationally has fallen from 904 in 2014 to 850 in 2022, while the number of reporters covering statehouses less than full time has risen markedly (from 688 to 874).

Different types of statehouse employment status

Full-time statehouse reporters: Reporters who are assigned full time to cover the statehouse year-round or when the legislature is in session. (Note: In the 2014 study, year-round and session-only reporters were separated in the final analysis. Full-time figures for 2014 have been recalculated for this report to include both year-round and session-only journalists.)

Part-time statehouse reporters: Reporters who cover the statehouse only some of the time, typically alongside other areas of coverage.

Student reporters/interns: Interns or college or university students who cover the statehouse, typically at a university-run news service or as a student intern at a news organization.

Other supporting staff: Staff who do not fit into any of the above categories, but nonetheless provide support to statehouse reporters, such as editors, producers or videographers.

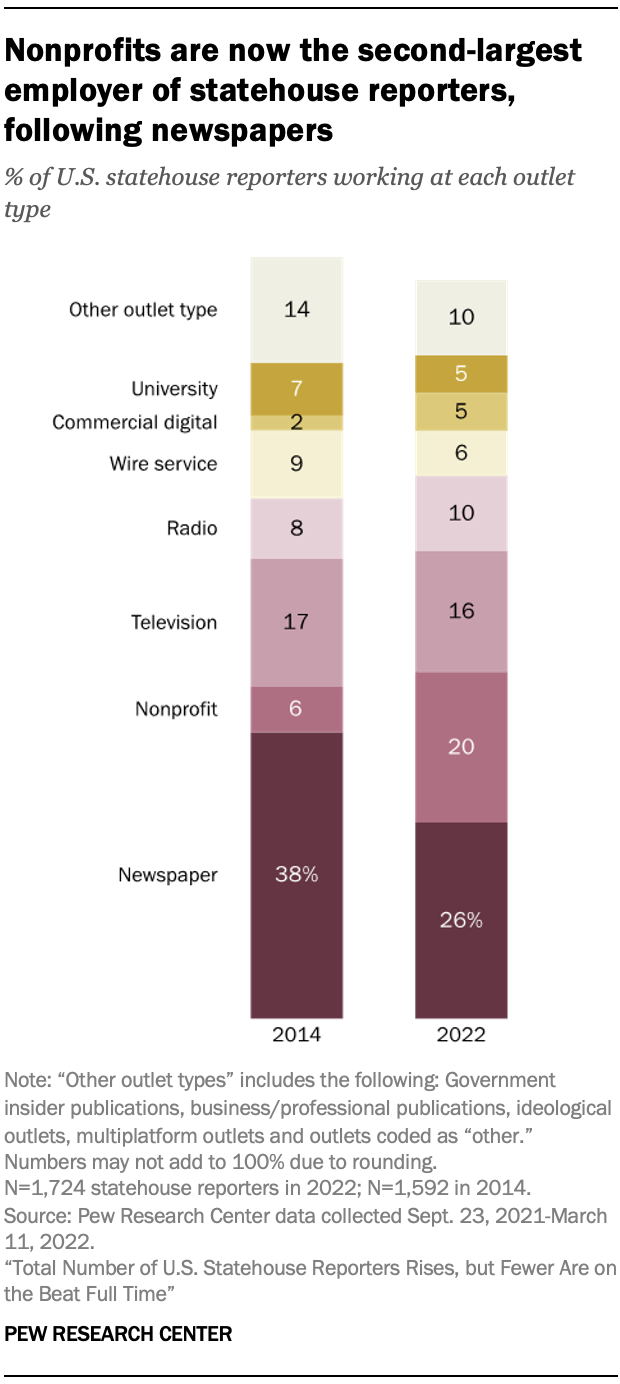

There has also been a significant shift in the types of outlets employing these reporters – if not a full changing of the guard. After years of staff cutbacks in the newspaper industry, nonprofit news outlets have moved in to fill a legacy media gap.

Nonprofit reporters alone (whether full time or less than full time) now constitute 20% of the statehouse corps, up from 6% in 2014.1 In total numbers, that translates to 353 statehouse reporters working for nonprofit news organizations in 2022, compared with 92 in 2014. Nonprofit statehouse reporters now make up the largest portion of the statehouse corps in 10 states, and the second largest in 17 states.

The overwhelming majority of these nonprofit news organizations either launched since 2014 or are new in employing statehouse reporters, and thus were not identified as a part of the reporting pool in the 2014 dataset. For example, States Newsroom launched in 2017 and has expanded to more than 20 states, Spotlight PA was founded in 2019 to cover the Pennsylvania state government, and CalMatters was founded in 2015 to cover the Capitol in California.

Newspaper statehouse staffing declined the most between the two studies, although this sector still accounts for the largest portion of reporters nationally. As of 2022, 448 statehouse reporters work at newspapers, making up 26% of the statehouse corps, down from 604 – 38% of the total – in 2014.

Changes in statehouse reporters vary by state

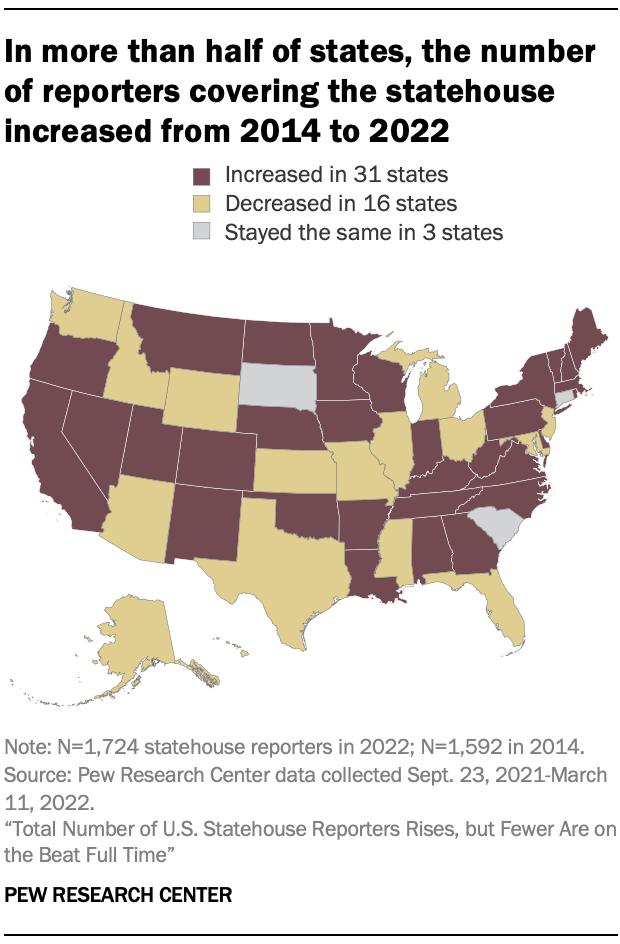

Although the total number of reporters covering statehouses increased overall, that is not the case for each individual state. In 31 states, the total number of statehouse reporters increased between 2014 and 2022, while about one-third of states – 16 in total – experienced decreases. Three states – Connecticut, South Carolina and South Dakota – retained the same overall numbers of statehouse reporters.

The largest increase and decrease at the state level – New Mexico and Missouri, respectively – are attributable to a major increase or loss of part-time or student reporters covering the statehouse. Still, some states also have experienced notable changes in the number of full-time statehouse reporters. This includes California, which has 21 more full-time reporters on the beat than in 2014, and Texas, where there are now 16 fewer full-time reporters covering the Capitol than there were eight years ago.

Challenges and changes to statehouse reporting brought on by COVID-19

Since the pandemic emerged in early 2020, COVID-19 has had a significant impact on statehouse reporting, shutting down capitols and at least temporarily scattering many reporters and legislators from their workplaces.

As part of this study, Pew Research Center conducted 24 interviews with individuals involved in statehouse coverage between August 2021 and February 2022. The majority of interviewees work at news outlets, but a few work as either legislative leaders’ chiefs of staff or as statehouse communications officials. In addition to other insights regarding changes in statehouse reporting, these interviews revealed several common threads about the impact COVID-19 has had on statehouse coverage and access.

According to these interviews, many legislatures have responded by substantially expanding live streaming of meetings and sessions, which allows for remote coverage while at the same time curtailing the ability of reporters and legislators to engage in person and build relationships. Some also told us that working remotely led them to reevaluate how to most efficiently do their jobs. Finally, a number of interviewees noted how the public policy debate over COVID-19 protocols became a major topic of coverage for journalists reporting on statehouses.

Chapter 4 includes details from the interviews. Remarks from interviewees also are included throughout the report to add context and personal experience to the quantitative data gathered in the accounting of statehouse reporters.

Coverage of Native American tribal governments

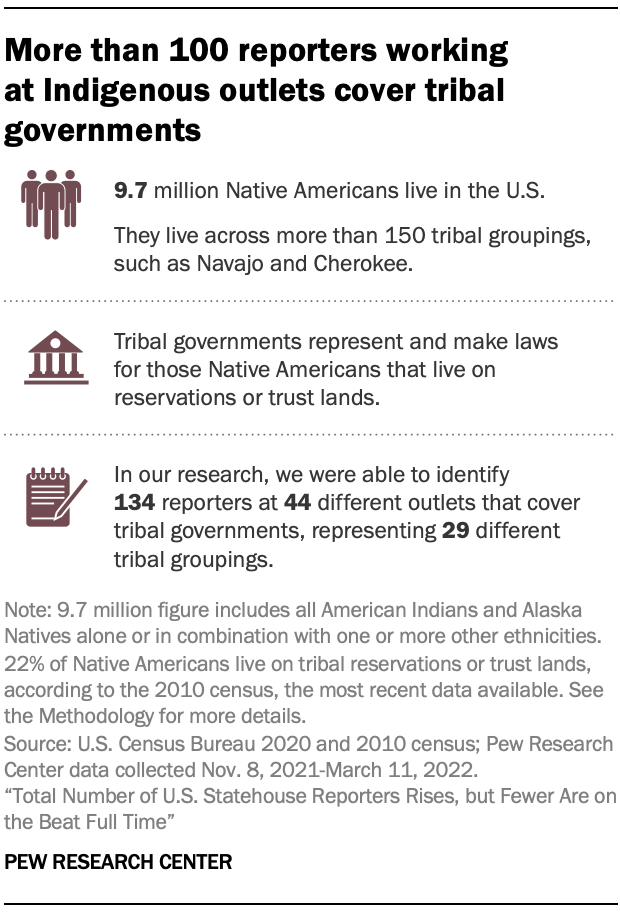

Within the United States, there are 9.7 million Native Americans (as of the 2020 U.S. census).2 About a quarter of Native Americans live on reservations or other trust lands, many of which have their own governments that exist alongside state and federal governments and can enact and enforce laws and regulations.3 As with other government activities, reporters can play a key role in informing citizens about the policy debates and legislative activity in these entities.

The study verified 134 reporters covering tribal governments across 44 outlets. Additionally, researchers interviewed eight journalists and editors with experience working at outlets that cover tribal governments. One key difference between the media organizations that cover U.S. statehouses and the Indigenous media organizations that cover Indigenous governments is the relationship between the media outlets and the governments they cover. Some of the outlets identified are connected in some way with the tribe itself, whether through funding or operations. Interviewees brought up press independence as a key issue for indigenous outlets covering tribal governments.