While increased polarization among Republicans and Democrats at both ends of the ideological spectrum has created a sense of unending gridlock in Washington, the parties face a different kind of challenge in the upcoming midterm elections and beyond: how to appeal to the majority of Americans who are somewhere in the political middle.

The recent Pew Research Center survey on polarization in U.S. politics drew a lot of attention to the fact that the bases of each party were more divided along ideological lines than at any point in the last two decades. But, as it has always been, it is still the political middle that determines elections, even in this polarized era.

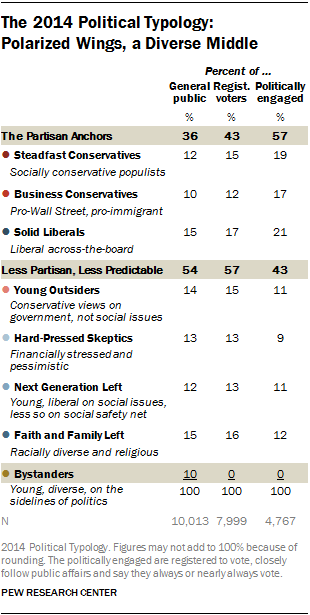

About 43% of registered voters can be identified as belonging to voting blocs that were “strongly ideological,” with 27% at the strongly conservative end of the spectrum and 17% being solid liberals, according to our political typology study, a follow-up to the polarization report.

But neither party has a base big enough to win national elections without broadening its appeal to the 57% of the electorate who are less partisan and less predictable.

The Typology survey laid out the challenges in doing so this way: “The political landscape includes a center that is large and diverse, unified by frustration with politics and little else. As a result, both parties face formidable challenges in reaching beyond their bases to appeal to the middle of the electorate and build sustainable coalitions.”

The groups in the center, whether leaning Republican or Democratic, are fragmented.

The group most likely to lean to the Republicans is what the Typology describes as Young Outsiders, 15% of registered voters. But while they lean to the GOP, that allegiance is not strong, and they diverge from the party on issues ranging from environmental regulation to liberal views on social issues.

Democrats face similar divides in the groups likeliest to be within their coalition. Hard-Pressed Skeptics, 13% of registered voters, are those who have been battered by the economy, and while resentful of government, back more generous government help for the poor and needy. The Next Generation Left, the 13% of voters who are young, relatively affluent on social issues, have reservations about the cost of social programs. And, the very religious and racially diverse Faith and Family Left, 16% of registered voters, are uncomfortable with the pace of social change.

So while Republicans and Democrats have come to increasingly hold different values, there remains enough variability in the middle of the electorate to insure political change. In other words, when we speak of political polarization, it is more a matter of Democrats and Republicans becoming more homogeneous in their values and basic beliefs than it is of the nation as a whole becoming fundamentally divided.

We only have to look to recent election outcomes to see the importance of the political middle. Between 2000 and 2012, a period of rapid growth in partisan polarization, the middle gave four victories to the GOP and three to the Democrats in nationwide elections. However, when it comes to primary elections, which are mostly decided by the bases of each party, greater partisan polarization does give greater advantage to more liberal and more conservative candidates, respectively.